Formazione & insegnamento, 23(03), 8186

Teaching and learning metacognitively with task-based activities: A case study with Chinese students of Italian

Insegnare e apprendere in modo metacognitivo attraverso attività task-based : Uno studio di caso con studenti cinesi di italiano

ABSTRACT

This paper presents a case study that analyzes the efficacy of integrating metacognitive strategies with Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) to improve the oral proficiency of Chinese students enrolled in the Marco Polo and Turandot Programs, who are learning Italian as a Second Language. The research utilizes the Teaching Speaking Cycle Pedagogical Model (Goh & Burns, 2012), involving L2 learners in a series of three distinct speaking tasks. A key component of the methodology was the systematic delivery of individual feedback, followed by the re-performance of the tasks. Critically, the study incorporated a dedicated metacognitive activity after the second task, explicitly prompting students to analyze and reflect on their own linguistic output and learning behavior. Data collection methods included audio recordings of the tasks and a final questionnaire assessing student perceptions. Findings indicate that this reflective approach significantly boosted learners’ self-correction and reduced performance anxiety, suggesting a marked improvement in the quality and organization of their linguistic output. The study argues that explicitly teaching metacognitive awareness is essential for promoting learner autonomy and self-regulation.

Il contributo presenta uno studio di caso che analizza l’efficacia dell’integrazione di strategie metacognitive con il Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) nel miglioramento della competenza orale di studenti cinesi iscritti ai Programmi Marco Polo e Turandot, impegnati nell’apprendimento dell’italiano come seconda lingua. La ricerca adotta il Teaching Speaking Cycle Pedagogical Model (Goh & Burns, 2012) e coinvolge apprendenti di L2 in una sequenza di tre compiti orali distinti. Un elemento centrale della metodologia è la restituzione sistematica di feedback individuali, seguita dalla ripetizione dei compiti. In particolare, dopo il secondo compito è stata introdotta un’attività metacognitiva dedicata, finalizzata a sollecitare esplicitamente la riflessione degli studenti sulla propria produzione linguistica e sui comportamenti di apprendimento. La raccolta dei dati ha incluso registrazioni audio dei compiti e un questionario finale sulle percezioni degli studenti. I risultati mostrano un incremento significativo dell’autocorrezione e una riduzione dell’ansia da prestazione, suggerendo un miglioramento nella qualità e nell’organizzazione della produzione orale. Lo studio sostiene che l’insegnamento esplicito della consapevolezza metacognitiva sia fondamentale per promuovere autonomia e autoregolazione nell’apprendimento linguistico.

KEYWORDS

Chinese university students, Italian teaching and learning, Metacognition in the language classroom, Task-based learning, Second language speaking competence, Marco Polo and Turandot Programs

Studenti universitari cinesi, Insegnamento e apprendimento dell’italiano, Metacognizione nella classe di lingua, Apprendimento task-based, Competenza orale in seconda lingua, Programmi Marco Polo e Turandot

AUTHORSHIP

This article is the result of the work of a single Author.

COPYRIGHT AND LICENSE

© Author(s). This article and its supplementary materials are released under a CC BY 4.0 license.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The Author declares no conflicts of interest.

RECEIVED

July 6, 2025

ACCEPTED

November 11, 2025

PUBLISHED ONLINE

December 31, 2025

1. Introduction

The present work shows a case study where task-based activities and metacognition techniques were used concurrently to further develop the speaking ability of a group of Chinese university students learning the Italian language in Italy. The teaching activity was settled around the use of the Teaching Speaking Cycle Pedagogical Model (Goh & Burns, 2012). Students participated in three oral tasks that were recorded. They received individual feedback and re-performed the same task which was also recorded. This second recording was also followed by personal feedback. Moreover, the third task was supported by the presentation and implementation of a metacognitive activity. In the final phase of the study the students filled in a questionnaire about their perceptions on the use of metacognition when learning a second language. All the feedback given was collected in three separate documents, one for each task, and was analyzed through the means of the software for qualitative analysis MAXQDA. Data are therefore presented and discussed considering the learning environment within which the research took place.

2. Theoretical underpinnings

2.1. Speaking skill

Speaking is one of the four language skills and it is a crucial one for personal, academic and professional success not only in one’s mother tongue but also in the case of a foreign or second language[1] learner. Differently from Chomsky (1957, 1965) who used the expression ‘linguistic competence’ to define implicit knowledge which allows speakers to both recognise and make grammar corrected utterances in their native language, communicative competence was specifically theorized by Hymes (1971) who defined it as the language skill necessary for communication and social interaction, thus indicating four judgments: possibility, feasibility, appropriateness and actual performance.

2.2. Components of speaking skill

In 1980, Canale and Swain identified four categories underlying communicative competence, namely grammatical competence, discourse competence, sociolinguistic competence and strategic competence. Grammatical competence refers to the use of lexical and morphosyntactic structures; discourse competence allows to connect sentences and make a meaningful series of utterances; sociolinguistic competence is the use of the proper socially accepted way of saying things, understanding the roles of the participants in the conversation and adequately interacting with them (Halliday, 1978); while the strategic competence is the ability to bring forward the communication process through the use of different strategic moves such as repetition, asking for clarification, circumlocution and so on. Furthermore, the output hypothesis (Swain, 1985) emphasizes the role of language production in noticing specific features of the target language thus fostering second language acquisition. Savignon (2002) adds to the concept of communicative competence the meaning-making aspect, especially when the communicative act is realized in an authentic environment.

2.3. Models of production and acquisition

The process of speech production is complex. In 1989, Levelt conceptualized a model for the process of speech production showing how complicated the skill actually is. His model takes into account three phases: conceptualization/preparation, formulation and articulation. These stages involve different processes and usually happen contemporaneously in the brain. Nonetheless, neuro linguistic studies are still investigating how the human brain processes speech and how oral competence is developed in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) (Danesi, 2003; Li et al., 2022; Mireskandari & Alavi, 2015; Namaziandostet al., 2019; Simmonds et al., 2011a; Simmonds et al., 2011b; inter alia).

Focusing on teaching/learning to speak in a foreign language, Goh and Burns (2012, p. 53) presented a model representing three interconnected aspects of second language oral competence: linguistic proficiency, fundamental speaking abilities and communication techniques. Grammatical, phonological, lexical and discourse knowledge are all part of language competence; fundamental skills include speech function, pronunciation and prosody, as well as interaction management, and discourse organization; while communicative strategies can be classified as cognitive, metacognitive and interactional.

2.4. Pedagogical challenges

As far as foreign or second language teaching goes, many instructors are fully aware of the importance of working on the speaking competence and implement speaking activities whenever feasible in their classrooms, compatibly with student numbers and other issues, such as time constraints and so on. As a matter of fact, speaking is crucial for second language learners given it is the one ability that allows interaction with other speakers (Hatch, 1978; Long, 1996; Nuzzo & Grassi, 2016; inter alia) and often is connected with integration in social life, not only personally but also professionally and/or academically. Nonetheless, speech production remains something volatile. In foreign language teaching/learning, writing and reading comprehension are the skills which are easier to assess by means of more objective exercises and tests, while listening comprehension and oral production can be considered more fugacious as can be deduced from the different opinions on how to teach and assess them (Garbati & Madi, 2015). Moreover, mainly because speaking is transient and ephemeral, even if in the language classroom speaking training practices are often part of the teaching praxis, very seldom is oral competence taught explicitly (Goh & Burns, 2012; Burns, 2019), which, according to Goldenberg’s studies (2008) reporting how explicitly teaching foreign or second language features (i.e., lexicon, morphosyntax, and so on) is crucial for acquisition. Spada and Lightbown’s research (2008) shows that the combination of explicit teaching and opportunity for real communication in the foreign or second language helps in the acquisition process. As mentioned above, speaking is not a simple activity, especially for foreign or second language learners, since it implies recalling lexicon from memory, framing it in the most adequate morphosyntactic way in the target language, whilst at the same time being socially and culturally appropriate (Bygate, 2005; Zhang et al., 2022). Cognitive, physical and socio-cultural processes underlie oral competence. In fact, as Burns (2019) also claims, referring to the model in Goh and Burns (2012): teaching speaking competence means “understanding the ‘combinatorial’ (Johnson, 1996, p. 155) nature of speaking, which includes the linguistic and discoursal features of speech, the core speaking skills that enable speakers to process and produce speech, and the communication strategies for managing and maintaining spoken interactions”. It is also demonstrated that scaffolding instruction (Gibbons, 2007) and peer, collective scaffolding (Donato, 1994; Ewald, 2005; Maybin et al., 1992) in speaking activities can sustain motivation and therefore language learning.

2.5. Task-based language teaching

The theorization of task-based language teaching (TBLT) started in the 1970’s and was developed even more in the 1980’s thanks to the work of Prabhu (1987). Embedded in the Communicative Approach, it focuses on real life tasks which need to be mediated by the language in order to be achieved, thus also fostering problem solving skills, critical thinking and cooperation. Ellis R. (2003) collects nine definitions taken from different scholars who all underline the importance for the learners of using their own linguistic resources to operate with the language, working with it, (grasping) the strong connection with real world activities, and the significance of the meaning in the linguistic outcome, Ellis’(2003:16) one of which is as follows:

“a workplan that requires learners to process language pragmatically in order to achieve an outcome that can be evaluated in terms of whether the correct or appropriate propositional content has been conveyed. To this end, it requires them to give primary attention to meaning and to make use of their own linguistic resources, although the design of the task may predispose them to choose particular forms. A task is intended to result in language use that bears a resemblance, direct or indirect, to the way language is used in the real world. Like other language activities, a task can engage productive or receptive, along with oral or written skills, and also various cognitive processes.”

This definition underlines the importance of the language objective proposed to students, its connection with reality and the fact that learners can make use of their own linguistic resources, their knowledge and competence in the second language, therefore becoming active participants who engage in the language acquisition process. This process is usually divided into three phases (Prabhu 1987; Estaire & Zanón 1994; Skehan 1996; Willis 1996; Lee 2000; inter alia): pre-task, task or main-task and post-task. In the pre-task phase the task is presented and the learners can plan out their response. Eventually, language models, specific vocabulary or morphosyntactic structures can be reviewed. During the main task phase the students are actually involved in the implementation of the task while in the post task, learners are guided to reflect on what they have done, after which, focus on form can be brought in. Nonetheless, different scholars have theorized the task phases differently—i.e., Nunan (2004) gives a very detailed six phase task realization; Martín Peris (2004) and Estaire (2011) propose a sequence in four phases. For the purpose of this study the three-phase task was used. Adding to all this, when trying to develop the oral production skill in second language learning, task activities and specifically task planning, where rehearsal is involved, can have a beneficial effect on fluency during the performance (Ellis, 2009, Gass et al.,1999; Skehan & Foster, 1999; inter alia). This is truer still when the planning and the oral repetition of the task is done in collaboration with peers.

2.6. Metacognitive awareness

Flavell defines metacognition as “knowledge and cognition about cognitive phenomena” and differentiates it into metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences and metacognitive strategies (Flavell, 1979, p. 906). Moreover, cognitive and sociocultural variables influence metacognition (Zhang & Zhang, 2013). Studies also show the beneficial influence of metacognition in language learning (Haque, 2018; Haukas et al., 2018; Graham & Macaro, 2008; Nakatani, 2005; Nguyen & Gu, 20123; Vandergrift & Tafaghodtari, 2010; Zenotz, 2012; inter alia) and it is reported that high proficiency learners usually make large use of metacognitive strategies (Lai, 2009; Liu, 2010; Phakiti, 2003; Radwan, 2011; inter alia). Different tools have been used to measure metacognition in language learning, qualitative ones such as self-reported instruments (i.e., think aloud protocol), but also quantitative ones, like questionnaires: i.e., the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI) (Schraw & Dennison, 1994) and the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) (Oxford, 1990). Research is suggesting that Mixed Method research (MM), which integrates qualitative and qualitative tools, would allow for better measurements of metacognition (Shraw, 2009). Moreover, explicit focus on metacognition seems to have a beneficial effect on metacognitive awareness (Lam, 2009; Nguyen & Gu, 2013; Vandergrift, 2002; Vandergrift & Tafaghodtari, 2010; Zenotz, 2012; inter alia) fostering Sustained Deep Learning (SDL).

2.7. The Teaching Speaking Pedagogical Cycle

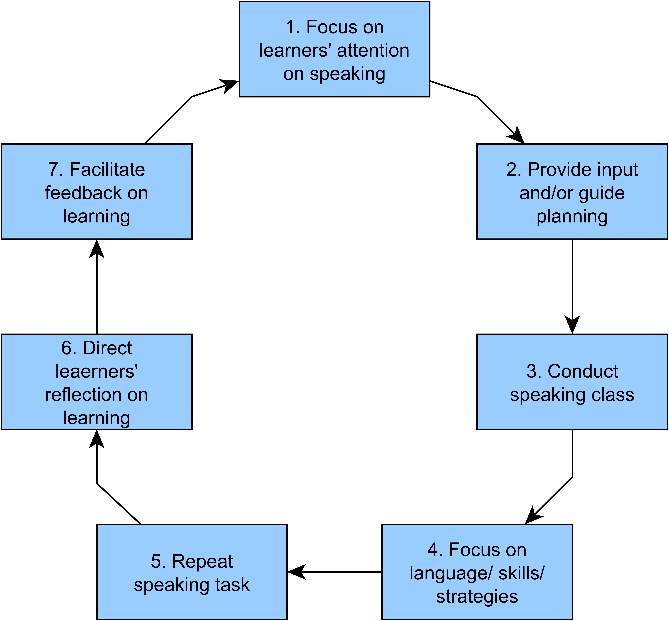

Theorized by Goh and Burns (2012), this pedagogical cycle incorporates three fundamental features: the explicit teaching of the speaking ability, a task-based approach and metacognition on the language learning process. As can be seen in the image below, the cycle is divided into seven stages: focusing the learners’ attention on speaking; providing input and/or guide planning; conducting a speaking task; focusing on language/skills/strategies; repeating the speaking task; directing the learners’ reflection on learning; facilitating the feedback on learning.

Figure 1. The Teaching Speaking Pedagogical Cycle (adapted from Goh & Burns, 2012).

Since this instrument corresponded to the aim of the teaching activity for its use of the task-based methodology, its emphasis on the oral competence and the presence of metacognitive reflection, it was decided to apply it.

3. Context and methodology

3.1. The context

The present study took place in an Italian course for Chinese university students held in Italy. These students participate in the “Marco Polo and Turandot Programs”, which are agreements between the Italian Universities Board of Deans (Conferenza dei Rettori delle Università Italiane, CRUI), the Ministry of Education, University and Research (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca, MIUR, nowadays MIM, Ministero dell’Istruzione e del Merito) and the Chinese government that started respectively in 2006 and 2009. Under the terms of the Marco Polo Program, Italian universities and Polytechnic universities provide places exclusively for Chinese students. The number of these places changes every year. The same goes for the Turandot Program, with the difference that in this case, places are provided by the institutions for Higher Training in Arts and Music (Alta Formazione Artistica Musicale e coreutica, AFAM). The requirements for participation in these programs are to have obtained 400/750 points on the gaokao (the Chinese national exams to enter university) and, for the art students, 300/750 points in the yikao (the Chinese national examination to enter art academies and conservatories). When applying for the visa at the Italian consular offices in the People’s Republic of China, these students must show they have the economic means to deal with life expenses in Italy. Additionally, they have to demonstrate the ability to return (usually by showing a return plane ticket) and they should have health insurance (Di Calisto et al., 2024). Another provision is the attendance of an at least 800 hours long Italian language course in Italy and to pass a B1 or B2 level (depending on the institution of pre-enrolment) of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2025) exams before enrolling in Italian universities, art academies or conservatories.

The students who participated in the research were members of these programmes: 60% were part of the Turandot Program (mainly music, art, design, etc.) and 40% of the Marco Polo Program (history, engineering, tourism management, etc.). At the moment when the study was carried out, their level of Italian competence was between A1 and A2. Twenty dyads participated in the first task, 18 in the second and 16 in the third.

3.2. The tasks

The choice of the task topics was based on their relevance for the needs of the learners (Nunan, 2004). In fact, the first was the enrollment for an Italian language proficiency exam which is mandatory for them to successfully enter the Italian higher education system. Students were each provided with a form used by one of the four certification centers in Italy (CELI, see Università per Stranieri di Perugia, 2025; Certit, see Università degli Studi Roma Tre, 2025; CILS, see Università per Stranieri di Siena, 2025; PLIDA, see Società Dante Alighieri, 2025). Learners were divided into pairs. During the pre-task, the aim of the activity was clarified, then the meaning of some words was explained via more high frequency synonyms that students of this level might be familiar with (namely, at this level of competence in Italian, students might know the word “indirizzo”, but not yet know the word “residenza” which is a more formal written form that is often used in forms). The task required learners to imagine a situation where one of them would go to a language school and together with the secretary would fill in the form, so the secretary would ask the student the questions needed to complete it. The learners had to firstly think of how the secretary would ask these questions, afterwards they would practice the dialogue and record it. Then they would swap roles and record again. The recordings, on their mobile devices, would be sent to the teacher. Feedback was sent to all the students individually by email. The feedback was calibrated according to the level: if it was an issue that students should be aware of, but did not use properly, a hint for correction was given; in cases where the mistakes were above the competence level, a correction would be given followed by the explanation. The language used in the feedback was mainly Italian, only otherwise too difficult explanation would be in Chinese, i.e., for words with similar meanings but different usages. After the first feedback, learners re-performed the task and recorded it again, sending it to the teacher for further feedback. After the repetition of the task, students were asked to answer five metacognitive questions:

- What have you learned from this activity?

- Was it difficult? Why?

- Did you like it? Why?

- In your opinion, was it useful? Why?

- How did you feel about working in couples?

Answers could be given both in Chinese and/or Italian: here the crucial point was for learners to be able to truly express themselves and at that moment, they might have not been competent enough in Italian to do so. For this reason, it was chosen to leave the participants free to choose the language of their response.

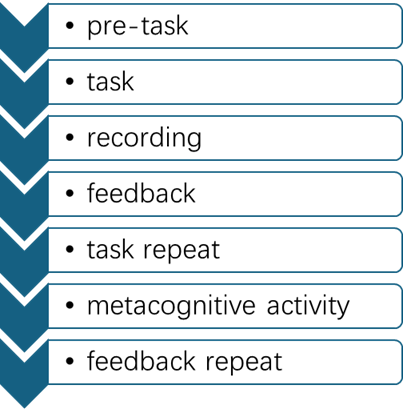

The modus-operandi for the three tasks followed the sequence just described above and it is also summarized in the flow-chart below.

Figure 2. Flow-chart of the sequence used for the Teaching Speaking Pedagogical Cycle.

For the second task, students had to think and design a possible interview for admission into the university or conservatory or art academy chosen. During the pre-task, there was a brain-storming of ideas about what teachers could possibly ask students in trying to understand which one of them could be a better choice for their school in order to make the right selection. Afterwards, students were required to prepare the answers to the questions they came up with and enact the role-play. The rest followed the routine outlined earlier: recording, feedback, task repetition and re-recording, metacognitive activity and feedback.

For the third and last task the hypothetical scenario envisaged that the students had been robbed and needed to go to the police station to report the theft. In the pre-task, the vocabulary for describing objects (colors, shapes, other descriptive adjectives or expressions) was reviewed through the means of ludic activities created with applications (i.e., Wordwall, 2025) with the purpose of being more engaging. After the lexicon revision, the task was introduced explaining the fictional situation and learners were asked to envision the scene where they would be at the police station and the police officer would ask them information about the theft: when, where and how it happened and what was inside the bag/backpack, and so on. As for the previous tasks the same cycle was followed. The only variation is that, with this task, a reflexive focus was added to the strategies used to complete the task. The decision to apply this reflective practice on this last task was dictated by the fact that it was believed that students would be familiar with the pedagogical speaking cycle by this time and so something new could be introduced. Therefore, before the implementation of the task, the instructor explained the concept of ‘strategy’ and clarified it with some examples, some of which involving language learning, then asked the learners to write down the strategies they would use to accomplish the task. Furthermore, this time, during the metacognitive activity, one question about strategies was included:

- Is reflection on strategies useful in learning Italian? Why?

In the following paragraph the collected data will be analyzed.

3.3. Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) to participate in this study and for their audio-recordings to be used in this study as well as for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

4. Data analysis

A thematic analysis (Alholjailan, 2012; Boyatzis, 1998; Braun & Clarke, 2006; Clarke & Braun, 2013; Javadi & Zarea, 2016; Nowell et al., 2017; Vaismoradi et al., 2013; inter alia) of the data was carried out by means of the software for qualitative analysis MAXQDA. The feedback given individually to students was assembled in a single document, resulting in six documents overall. The answers to the metacognitive questions were also analyzed. Therefore, a total of nine documents were codified through multiple cycle coding. The analysis conducted consisted of bottom up, inductive, research where patterns or themes emerged from data itself. The six-phase guide provided by Braun and Clarke (2006) was followed: first of all, the researcher became familiar with the data, successively the codes were assigned. Codes were then merged into main themes. Afterwards, the themes were revised and defined resulting in the writing of this work. The outcome of the process can be found in the appendix.

4.1 The analysis of the feedback

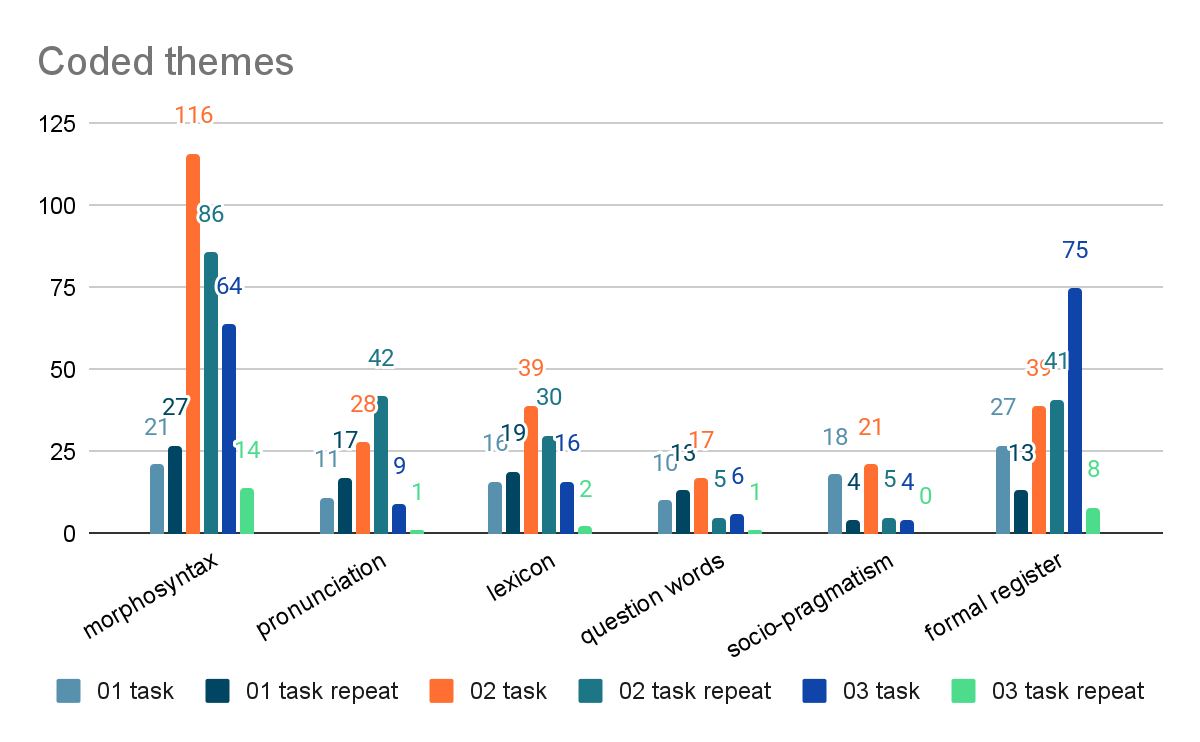

In the six feedback documents, the researcher coded the following features in the interlanguage of the students:

- Morphosyntax, which was divided among gender and number agreement in noun phrase, verbal conjugation, other (i.e., improper preposition use, etc.).

- Pronunciation, which included word pronunciation as well as fluency and confusion between words with similar sounds (i.e., “paese” and “pesce”, “molto” and “morto”, “perso” and “preso”, etc.).

- Lexicon (i.e., the undifferentiated use of “bene”, “buono”, “bello” and “bravo”, the use of “guardare” instead of “leggere” and “perdere” instead of “rubare” which are transfers from L1).

- Question words (i.e., “che cosa è il tuo numero di telefono?” instead of “qual è il tuo numero di telefono?”), which the author decided not to include in other codes due to its high frequency.

- Contextualization/socio-pragmatic norms (i.e., salutation at the beginning of the dialogue, or other cultural norms that are pertinent in certain specific communicative situations). This code was used whenever the discourse social and cultural norms were not properly followed. For example, when the dialogue started without opening salutation.

- Text coherence and formal/informal register (i.e., the use of the honorific “Lei”), even though the author decided not to include this feature in other codes for its high frequency throughout the feedback.

In the graph below (see Figure 3) it can be noticed that almost always the feedback of the repetition shows improvement compared to the feedback of the first registration. One striking exception is the pronunciation of the remake of the second task. This could be explained as students focusing on meaning and/or on the use of specific vocabulary to the detriment of pronunciation.

Figure 3. Feedback main issues (coded themes).

4.2. The analysis of the metacognitive answers

The answers to the metacognitive questions allow the researcher to understand students’ perception about the pedagogical cycle and the three different tasks. All together 29 answers were collected. The following chart shows the tasks after which they were gathered and the language used.

Task | Chinese | Italian | Total |

1 - filling in a form to enrol in an Italian exam | 3 | 6 | 9 |

2 - interview for academic admission | 3 | 8 | 11 |

3 - describing a stolen bag to the police | 3 | 6 | 9 |

Total | 9 | 20 | 29 |

Table 1. Synopsis chart of the answers given to the metacognitive questions.

As can be seen, Italian was used more than the students’ mother tongue. When analyzing the answers, the most difficult task was considered the second one, while the other two were perceived as “somewhat hard”. When asked to motivate their answers, students point at the small volume of vocabulary known, to the scarce development of the listening comprehension skill: “因为我的意大利词汇量有限以及我的听力水平还有待提 (because my Italian vocabulary is limited and my listening skills need to be improved), “perché so come rispondo le domande di professore in cinese, ma non so come tradurre in italiano, ci sono tante parole dell’arte non conosco, devo memorizzarle” (because I know not to reply to a professor in Chinese, but I don’t know how to translate into Italian, there are many words that I do not know, I must memorize).

At the same time the second task was felt to be both the most liked and the most useful. Some of the motivation given was the connection to real life: “perché posso imparare molto da questo tipo di conversazioni nella vita reale” (because I can learn a lot from this type of conversation in real life); for improving listening and speaking skills: “因为可以提高我们的听力和口语” (because it can help to improve listening and speaking); for the need to be able to sustain an interview to be admitted in the higher education system in Italy: “perché il colloquio è molto importante per noi deviamo impararla” (because the interview is really important and we need to learn it); to sustain language learning motivation: “Perché è utile e anche interessante, quando partecipo delle attività che diverse dalle lezioni quotidiane posso tenere il mio passione per la lingua italiana” (because it is useful and also interesting, when I participate in activities that are different from everyday classes I can maintain my passion for the Italian language); and also because it can help to live a better life: “penso che aiutarci a vivere una vita meglio” (I think it can help us to live a better life). One adds that they like this active way of learning: “Perché mi piace questo modo attivo di apprendere” (because I like this active way of learning). One student also highlights the opportunity the second task gave them to understand some cultural differences in facing an interview, emphasizing the intercultural aspects that this activity helped unveil: “Perché ho partecipato tanti colloqui in Cina, ma ci sono differenze e adesso posso capire tutto due bene” (because I participated in many interviews in China, but there are differences and now I can understand both well). Moreover, some participants recognize that not only are these activities promoting language learning, but also relationships with the other classmates: “per non solo posso imparare l’italiano ma posso anche comunicare con i miei compagni di classe” (not only because I can learn Italian but also I can communicate with my classmates).

In fact, cooperation with the partner was mainly considered good: 77% (24/31) coded segments reported symbiotic working experiences during the implementation of the tasks: “很高兴能和同学多交流 ” (I was happy to be able to communicate more with the classmates), “collaborando con i miei compagni di classe posso fare progressi e allo stesso tempo possa anche aiutare i miei compagni di classe” (cooperating with my classmates I can make progress and at the same time I can also help my classmates), “和同学们合作可以互相学习,互相提高” (cooperating with the classmates we can learn from each other, we can improve each other). On the other hand, the reports about bad cooperation seem to stem from personal characteristics and feelings: “仅对我个人来说我更喜欢一个人解决问题” (for me personally, I prefer to settle questions by myself), “和同学一起合作让我有点紧张” (cooperating with classmates makes me nervous).

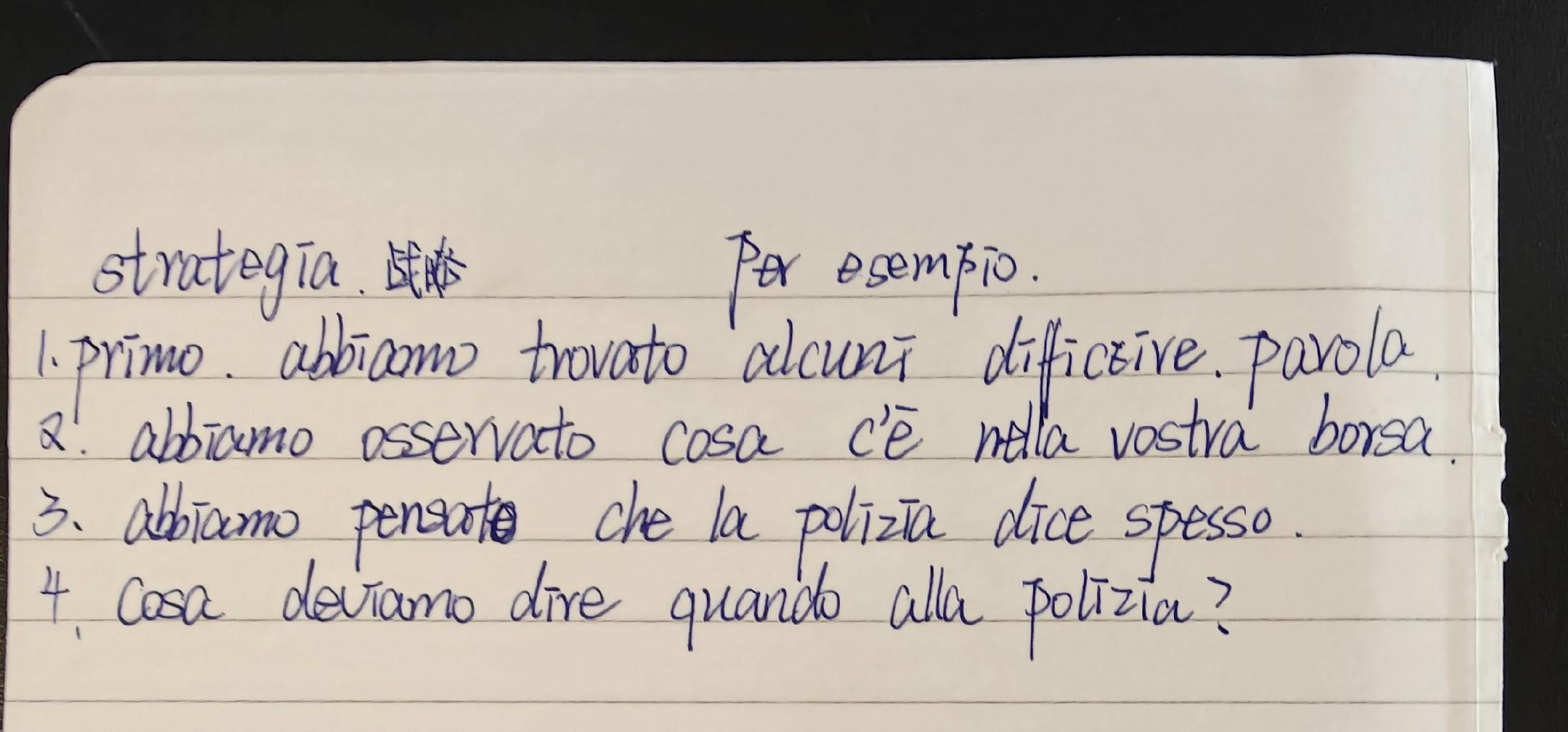

4.3. Strategies used

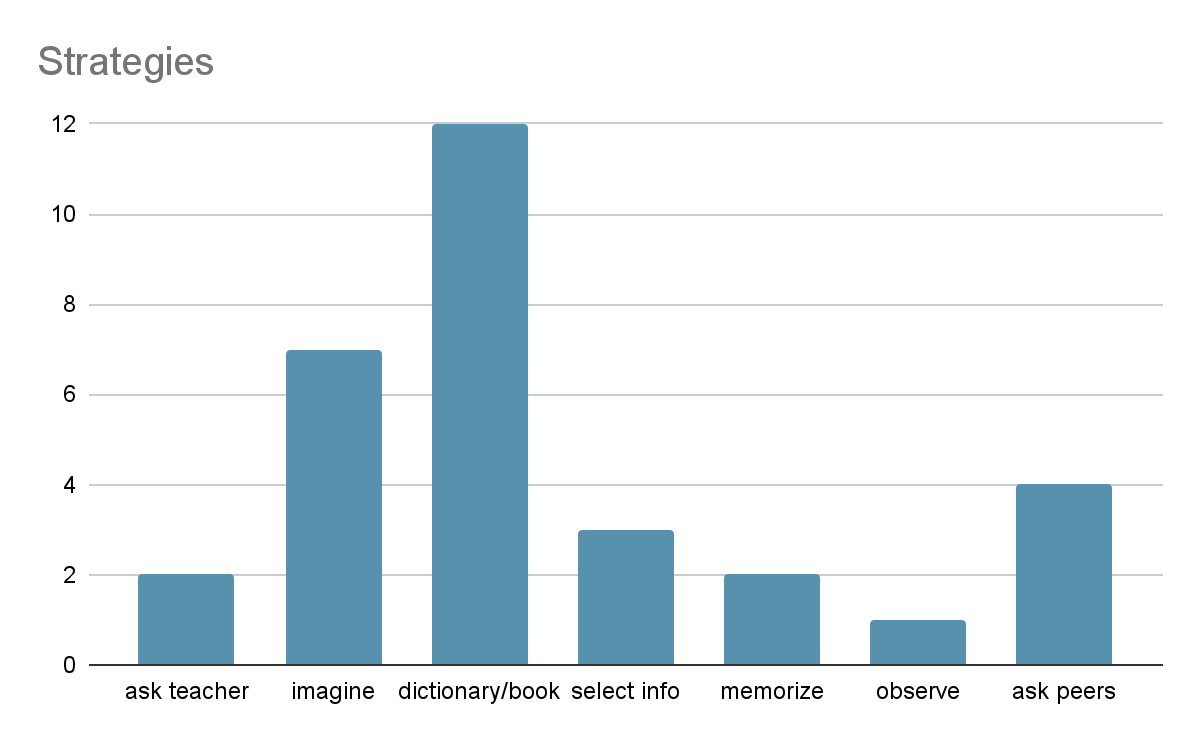

As mentioned earlier (Section 3.2) during the last task, there was explicit work on strategies. Students were asked which strategies they used to accomplish the task.

Figure 4. An example of students notes about the strategies used. Translation of the text in the image: “(1st row) Strategy, for example; (text) 1. first. We looked for some difficult words. 2. We observed what was inside our bags. 3. We thought about what the police often say. 4. What do we need to say when we are at the police (station)?”

According to the notes of the participants, the strategies used to complete the task were the following: ask the teacher (2), imagine the situation (7), look in the dictionary and/or textbook for references (12), select the information (3), memorize (2), observe (1), consult peers (4). There follows a chart showing the occurrence of the strategies as found in the students notes. The most used strategy involves looking for vocabulary or morphosyntactic structures either in the dictionary or in the textbook. The second is the use of imagination to picture the situation where the task takes place, followed by discussion with the classmates.

Figure 5. Strategies used to complete the tasks.

When asked if explicit acknowledgment of the strategies used to accomplish the task was perceived as useful or not, six students believed it was: “secondo me è importante. perché la mia lingua non buono,bisogno di un strategia” (in my opinion, it is important. Because my language is not good, I need a strategy), “Penso che gli studenti possano migliorare attraverso la pratica, ma se desiderano progredire in vari aspetti in una singola lezione o in un breve periodo di tempo, devono creare una strategia dettagliata ed efficace in anticipo” (I think that students can improve through practice, but if they wish to progress in different aspects in a single lesson or in a short period of time, they need to create a detailed and efficient strategy before); while three did not share the same opinion: “我个人认为战略的作用不是很大” (personally I believe the use of strategies is not big). Some admit that they had never thought about strategies before: “Ho imparato ad usare le strategie. Raramente pensavo alla strategia prima” (I learned to use strategies. Rarely I thought about strategy before).

5. Discussion and conclusions

According to Coleman and Goldenberg (2009), second language learners should be given opportunities to use the target language for genuine and practical objectives which is embedded in task-based methodology (Cortés Velásquez & Nuzzo, 2018; Ellis, R. 2003 and 2009; Gass et al., 1999; Long, 2015; inter alia). When planning a task it is also crucial to take into consideration the learners’ needs and context. The Teaching Speaking Pedagogical Cycle is a powerful tool that allows for all that and gives a mixture of both social and functional motivation (Burns, 2019:5). Specifically, the results showed an objective improvement in the re-performance task recordings and overall student satisfaction, challenging the stereotype of the passive Chinese student (Cortazzi & Jin, 2002 and 2006; D’Annunzio, 2009; Moth-Smith et al., 2011; Rao, 1996; inter alia), as participants demonstrated they valued activities that stimulate critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Pinello 2018; Scolaro, 2020; Wang, 2007).

Moreover, the context of the Marco Polo and Turandot Programs implies a specific and demanding Italian learning trajectory: students must achieve a B1 or B2 level of the CEFR to be eligible for university enrollment. The analysis highlights that, while learners appreciated the real-life tasks, they often started the language learning process with an A1-A2 level competence that requires focused effort to quickly reach the necessary linguistic proficiency for university-level study in Italian.

The metacognitive responses and feedback analysis clearly identified the main linguistic obstacles affecting their trajectory: difficulties in morphosyntax (verbs conjugations, noun phrase agreement and so on), specific vocabulary use (often due to L1 interference), and inadequate socio-pragmatic norms required in formal settings. These obstacles often stem from pre-existing learning styles and mechanisms, where students tend to favor search-based and memorization strategies but need to integrate these with active reflection on their oral production.

Therefore, success in navigating their specific learning trajectory requires an approach that not only provides practice through TBLT based activities, but actively fosters reflection. The integration of metacognition proved essential in developing learning self-regulation and supporting students in overcoming their specific difficulties (Zhang D & Zhang, 2019).

In conclusion, although managing the small case study presented some challenges, such as student absences, the evidence suggests that the combination of task-based activities and metacognitive reflection is fundamental in making Marco Polo and Turandot students not only more linguistically competent, but also more autonomous and aware of their own learning process.

Endnotes

In this article ‘second language’ means any language that can not be considered a person’s mother tongue. Moreover, in this work, foreign and second language are used as synonyms, in the sense of languages different from the mother tongue of the subject (L ≠ L1) (Balboni, 2012: Celentin, 2024; inter alia). ↑

References

Alholjailan, M. I. (2012). Thematic analysis: A critical review of its process and evaluation. West East Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1), 39–47.

Balboni, P. E. (2012). Le sfide di Babele: Insegnare le lingue nelle società complesse. UTET.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burns, A. (2019). Concepts for teaching speaking in the English language classroom. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network Journal, 12(1), 1–11. Retrieved 2025-11-11, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1225673

Bygate, M. (2005). Oral second language ability as expertise. In K. Johnson (Ed.). Expertise in second language learning and teaching (pp. 104–127). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230523470_6

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1–47.

Celentin, P. (2024). L’italiano come Lx: La diversità linguistica come vantaggio per l’apprendimento. Bollettino ITALS, 106, 3–29. Retrieved 2025-11-11, from https://www.itals.it/sites/default/files/pdf-bollettino/novembre2024/CELENTIN_03.pdf

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. Mouton.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. MIT Press.

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning.

Coleman, R., & Goldenberg, C. (2009). What does research say about effective practices for English learners? Introduction and part 1: Oral language proficiency. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 46(1), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2009.10516683

Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (2002). Cultures of learning, the social construction of educational identities. In D. C. S. Li (Ed.). Discourses in search of members: In honor of Ron Scollon (pp. 47–75). American Universities Press. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137296344_1

Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (2006). Changing practices in Chinese cultures of learning. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 19(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310608668751

Cortés Velásquez, D., & Nuzzo, E. (Eds.). (2018). Il task nell’insegnamento delle lingue: Percorsi tra ricerca e didattica al CLA di Roma 3. Roma TrE-Press.

Council of Europe. (2025). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). Retrieved 2025-12-20, from https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/home

Danesi, M. (2003). Second-language teaching: View from the right side of the brain. Kluwer.

(2024). VIII Convegno sui Programmi governativi Marco Polo e Turandot: 30 gennaio 2024. Uni-Italia. Retrieved 2025-11-11, from https://uni-italia.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/VIII-Convegno-MPT2024.pdf

Donato, R. (1994). Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J. P. Lantolf, & G. Appel (Eds.). Vygotskian approaches to second language research (pp. 33–56). Ablex.

D’Annunzio, B. (2009). Lo studente di origine cinese. Guerra.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based language teaching: Sorting out the misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00231.x

Estaire, S., & Zanón, J. (1994). Planning classwork: A task-based approach. Heinemann.

Ewald, J. (2005). Language-related episodes in an assessment context: A “small-group quiz”. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 61(4), 565–586.

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Garbati, J. F., & Mady, C. J. (2015). Oral skill development in second languages: A review in search of best practices. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(9), 1763–1770. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0509.01

Gass, S., Mackey, A., Alvarez-Torres, M. J., & Fernández García, M. (1999). The effects of task repetition on linguistic output. Language Learning, 49(4), 549–581.

Gibbons, P. (2007). Mediating academic language learning through classroom discourse. In J. Cummins, & C. Davison (Eds.). International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 701–718). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46301-8_46

Goh, C. M., & Burns, A. (2012). Teaching speaking: A holistic approach. Cambridge University Press.

Goldenberg, C. (2008). Teaching English language learners: What the research does—and does not—say. Retrieved 2025-11-11, from https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/goldenberg.pdf

Graham, S., & Macaro, E. (2008). Strategy instruction in listening for lower-intermediate learners of French. Language Learning, 58(4), 747–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2008.00478.x

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic. Edward Arnold.

Haque, M. M. (2018). Metacognition: A catalyst in fostering learner autonomy for ESL/EFL learners. Korea TESOL Journal, 14(1), 181–202. Retrieved 2025-11-11, from https://koreatesol.org/content/korea-tesol-journal-14-1

Hatch, E. M. (Ed.). (1978). Second language acquisition: A book of readings. Newbury House Publishers.

Haukas, Å., Bjørke, C., & Dypedahl, M. (2018). Introduction. In Å. Haukas, C. Bjørke, & M. Dypedahl (Eds.). Metacognition in language learning and teaching (pp. 1–10). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351049146

Hymes, D. H. (1971). On communicative competence. University of Philadelphia Press.

Javadi, M., & Zarea, M. (2016). Understanding thematic analysis and its pitfalls. Journal of Client Care, 1(1), 33–39.

Johnson, K. (1996). Language teaching and skill learning. Blackwell.

Lai, Y. C. (2009). Language learning strategy use and English proficiency of university freshmen in Taiwan. TESOL Quarterly, 43(2), 255–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00167.x

Lam, W. Y. (2009). Examining the effects of metacognitive strategy instruction on ESL group discussions: A synthesis of approaches. Language Teaching Research, 13(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168809103445

Lee, J. (2000). Task and communicating in language classrooms. McGraw-Hill.

Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. MIT Press.

Li, S., Hanafiah, W., Rezai, A., & Kumar, T. (2022). Interplay between brain dominance, reading, and speaking skills in English classrooms. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 798900. Article number: 798900. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.798900

Liu, H. J. (2008). A study of the interrelationship between listening strategy use, listening proficiency levels, and learning style. ARECLS, 5, 84–104. Retrieved 2025-11-11, from https://research.ncl.ac.uk/media/sites/researchwebsites/arecls/liu_vol5.pdf

Long, M. (1996). The role of linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. Ritchie, & T. Bhatia (Eds.). Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413–468). Academic Press.

Long, M. (2015). Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching. Wiley-Blackwell.

Maybin, J., Mercer, N., & Steirer, B. (1992). “Scaffolding”: Learning in the classroom. In K. Norman (Ed.). Thinking voices: The work of the national oracy project (pp. 186–196). Hodder & Stoughton.

Mireskandari, N., & Alavi, S. (2015). Brain dominance and speaking strategy use of Iranian EFL learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 4, 72–79. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.3p.72

Mott-Smith, J. A., Jin, L., & Cortazzi, M. (2011). Researching Chinese learners: Skills, perceptions and intercultural adaptations. Applied Linguistics, 32(5), 581–584. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amr035

Nakatani, Y. (2005). The effects of awareness-raising training on oral communication strategy use. The Modern Language Journal, 89(1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0026-7902.2005.00266.x

Namaziandost, E., Shatalebi, V., & Nasri, M. (2019). The impact of cooperative learning on developing speaking ability and motivation toward learning English. Language Education, 5, 83–101. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2019.9809

Nguyen, L. T. C., & Gu, Y. (2013). Strategy-based instruction: A learner-focused approach to developing learner autonomy. Language Teaching Research, 17(1), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168812457528

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Nuzzo, E., & Grassi, R. (2016). Input, output e interazione nell’insegnamento delle lingue. Bonacci.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Heinle & Heinle.

Phakiti, A. (2003). A closer look at the relationship of cognitive and metacognitive strategy use to EFL reading achievement test performance. Language Testing, 20(1), 26–56. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532203lt243oa

Pinello, V. (2018). Percorsi di grammatica valenziale con apprendenti sinofoni. In Y. Chen, M. D’Agostino, V. Pinello, & L. Yang (Eds.). Fra cinese e italiano: Esperienze didattiche (pp. 69–115). Luxograph.

Prabhu, N. (1987). Second language pedagogy. Oxford University Press.

Radwan, A. A. (2011). Effects of L2 proficiency and gender on choice of language learning strategies by university students majoring in English. Asian EFL Journal, 13(1), 114–162.

Rao, Z. H. (1996). Reconciling communicative approaches to the teaching of English with traditional Chinese methods. Research in the Teaching of English, 30, 458–471.

Savignon, S. J. (2002). Communicative language teaching: Linguistic theory and classroom practice. Retrieved 2025-11-11, from https://www.academia.edu/8930891/Communicative_Language_Teaching_Linguistic_Theory_and_Classroom_Practice

Schraw, G. (1994). The effect of metacognitive knowledge on local and global monitoring. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1013

Schraw, G. (2009). A conceptual analysis of five measures of metacognitive monitoring. Metacognition and Learning, 4(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-008-9031-3

Scolaro, S. (2020). Il profilo dello studente cinese dei Programmi Marco Polo e Turandot (anno 2019). Italiano LinguaDue, 12(2), 137–159. https://doi.org/10.13130/2037-3597/14978

Simmonds, A. J., Wise, R. J., Dhanjal, N. S., & Leech, R. (2011). A comparison of sensory-motor activity during speech in first and second languages. Journal of Neurophysiology, 106, 470–478. Year suffix: 2011b. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00343.2011

Simmonds, A. J., Wise, R. J., & Leech, R. (2011). Two tongues, one brain: Imaging bilingual speech production. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, Article 166. Year suffix: 2011a; Article number: 166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00166

Skehan, P. (1996). Second language acquisition research and task-based instruction. In J. Willis, & D. Willis (Eds.). Challenge and change in language teaching (pp. 17–30). Heinemann.

Skehan, P., & Foster, P. (1999). The influence of task structure and processing conditions on narrative retellings. Language Learning, 49(1), 93–120.

Società Dante Alighieri. (2025). PLIDA: Conosci la lingua italiana? Certificalo con un esame PLIDA. Retrieved 2025-12-20, from https://plida.dante.global/it

Spada, N., & Lightbown, P. M. (2008). Form-focused instruction: Isolated or integrated?. TESOL Quarterly, 42(2), 181–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00115.x

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. Gass, & C. Madden (Eds.). Input and second language acquisition (pp. 235–253). Newbury House.

Università degli Studi Roma Tre. (2025). Certificazione dell’italiano come lingua straniera: CertIT. Retrieved 2025-12-20, from https://certificazioneitaliano.uniroma3.it/

Università per Stranieri di Perugia. (2025). CELI (Certificati di Lingua Italiana). Retrieved 2025-12-20, from https://www.unistrapg.it/it/certificati-di-conoscenza-della-lingua-italiana/celi-certificati-di-lingua-italiana

Università per Stranieri di Siena. (2025). Centro CILS. Retrieved 2025-12-20, from https://cils.unistrasi.it/

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Vandergrift, L. (2002). ‘It was nice to see that our predictions were right’: Developing metacognition in L2 listening comprehension. Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue canadienne des langues vivantes, 58(4), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.58.4.555

Vandergrift, L., & Tafaghodtari, M. H. (2010). Teaching L2 learners how to listen does make a difference: An empirical study. Language Learning, 60(2), 470–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00559.x

Wang, T. (2007). Understanding Chinese culture and learning. In P. Jeffery (Ed.). AARE Conference 2006 papers (pp. 1–14). Australian Association for Research in Education.

Willis, J. (1996). A flexible framework for task-based learning. In J. Willis, & D. Willis (Eds.). Challenge and change in language teaching (pp. 235–256). Heinemann.

Wordwall. (2025). Wordwall: Create better lessons quicker. Retrieved 2025-12-20, from https://wordwall.net/

Zenotz, V. (2012). Awareness development for online reading. Language Awareness, 21(1–2), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2011.639893

Zhang, D., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Metacognition and self-regulated learning (SRL) in second/foreign language teaching. In X. Gao (Ed.). Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 883–897). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58542-0_47-1

Zhang, L. J., & Zhang, D. (2013). Thinking metacognitively about metacognition in second and foreign language learning, teaching, and research: Toward a dynamic metacognitive systems perspective. Contemporary Foreign Language Studies, 396(12), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-8921.2013.12.010

Zhang, W., Zhao, M., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Understanding individual differences in metacognitive strategy use, task demand, and performance in integrated L2 speaking assessment tasks. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.876208