Formazione & insegnamento, 23(03), 8185

Democratic Engagement and Transformative Inclusion: Insights from Italy’s 0–6 Early Childhood Education and Care Sector

Partecipazione democratica e modello trasformativo dell’inclusione: Riflessioni dal settore dell’educazione e cura della prima infanzia 0–6 in Italia

ABSTRACT

This study presents preliminary results from the “Pensare IN Grande / ThinkINg Big” project, based on a nationwide survey of Italian early childhood professionals. Anchored in the Council of Europe’s democratic competencies framework and Hackbarth and Martens’ model of “inclusion as transformation,” the ongoing study explores inclusive practices in 0–6 education settings. Preliminary findings highlight a strong culture of welcome and collaboration, alongside challenges in accessibility, infrastructure, and specialized training. The discussion calls for systemic investment, reflective professional development, and participatory governance to support inclusive education across Italy’s early years landscape.

Il presente studio illustra i risultati preliminari del progetto “Pensare IN Grande / ThinkINg Big”, basato su un sondaggio nazionale condotto tra i professionisti italiani che operano nel settore della prima infanzia. Lo studio, attualmente in corso, si fonda sul quadro delle competenze democratiche lanciate dal Consiglio d’Europa e sul modello di “inclusione come trasformazione” di Hackbarth e Martens, esplorando le pratiche inclusive nei contesti educativi per la prima infanzia, dalla nascita ai sei anni di età. I risultati preliminari evidenziano una forte cultura dell’accoglienza e della collaborazione, accanto a sfide in termini di accessibilità, infrastrutture e formazione specializzata. Dalla discussione emergono la necessità di investimenti sistemici, di uno sviluppo professionale riflessivo, nonché di una governance partecipativa al fine di sostenere l’istruzione inclusiva nel contesto della prima infanzia in Italia.

KEYWORDS

Democratic education, Transformative inclusion, ECEC professional development, Inclusive practices in ECEC

Educazione democratica, Inclusione trasformativa, Sviluppo professionale nella prima infanzia, Pratiche inclusive nella prima infanzia

AUTHORSHIP

Section 1 (V. Macchia, S. Torri); Sections 2–5 (V. Macchia); Sections 5.1–5.3 and Sections 6–8 (S. Torri); Section 9 (V. Macchia, S. Torri). This contribution is the result of extensive work and was conceived jointly by the two authors.

COPYRIGHT AND LICENSE

© Author(s). This article and its supplementary materials are released under a CC BY 4.0 license.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Competence Centre of School Inclusion, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano (Italy)

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

RECEIVED

July 5, 2025

ACCEPTED

November 25, 2025

PUBLISHED ONLINE

November 25, 2025

1. Introduction

Inclusive education goes beyond simply bringing together children with and without special needs in shared learning spaces. It requires a deep transformation of pedagogical and didactic approaches—redefining both the goals and the processes of early childhood education. Rooted in the belief that such transformation must begin as early as possible, inclusive education aims not only to accommodate diversity, but to actively shape the educational environment into a driver of long-term social change. At the same time inclusive early childhood education is inseparable from the cultivation of democratic competencies that empower children to participate actively in society (see Brandolini, 2024, for a comprehensive overview).

This article integrates theoretical, normative, and empirical perspectives to examine how inclusive education is interpreted and enacted in practice.

Bearing in mind these two dimensions of inclusive early childhood education—its role in both cultivating democratic competencies and driving transformative change—this article presents the inter-university project “Pensare IN Grande / ThinkINg Big”. Following a review of key studies on early childhood education and care (ECEC) with a focus on inclusion—highlighting both emerging opportunities and areas still requiring development—the current Italian legislative landscape is examined, with attention to recent reforms and evolving interpretations of inclusion. The project is subsequently introduced, including its origins, objectives, and policy framework, along with preliminary findings from a questionnaire administered to professionals across the 0–6 sector, such as teachers, educators, and other key actors. The article concludes with a reflection on the main strengths and persistent challenges identified and proposes actionable directions for practice and policy aligned with the inclusive vision outlined.

2. Fostering Democratic Competencies and Transformative Inclusion in Early Childhood Education and Care

2.1. The Foundation of Democratic Competencies

Inclusive early childhood education and care is inseparable from the cultivation of democratic competencies that empower children to participate actively in society. The Council of Europe (2018) defines these competencies as a combination of values, attitudes, skills, and knowledge—including critical understanding—that support human development within a democratic society. Individuals grow by cultivating diversity, equity, and justice (values); by maintaining an openness to other perspectives and a disposition toward tolerance (attitudes); by developing autonomy, empathy, cooperation, and conflict-resolution abilities (skills); and by acquiring knowledge that is inseparable from the critical capacity to sustain and apply it (knowledge and critical understanding) (Council of Europe, 2018).

This conceptual foundation is further reinforced by the European Sustainability Competence Framework by Bianchi et al. (2022), which identifies four core areas:

“Embodying Values: Educators and institutions must model fairness, respect, and solidarity in everyday interactions. Accepting Complexity:Children learn to navigate diverse perspectives and understand interconnected social and environmental challenges. Acting Sustainably: Practices foster stewardship of resources, guiding children to make choices that balance present needs with future generational equity. Shaping the Future: Young learners are encouraged to envision and co‐create more just inclusive communities” (Bianchi et al., 2022, pp, 17–27).

While not explicitly listing implementation strategies, the framework supports practical application through its emphasis on engaging with multiple perspectives, fostering intersectoral cooperation, and encouraging participatory, community-centred approaches to sustainability learning (pp. 23, 27, 29). These principles are particularly consistent with inclusive educational practices that value collaboration, voice, and shared responsibility.

2.2. Hackbarth’s Model: Inclusion as Transformation

Alongside this normative and strategic foundation, Hackbarth’s (2017) empirical research offers a complementary, practice-oriented perspective. Together with the theoretical work developed with Martens, (2018) the German scholar developed the concept of ‘inclusion as transformation,’ which frames inclusion as a fundamental reconfiguration of pedagogy, classroom relationships, and the learning environment. Although Hackbarth’s research primarily focuses on primary school settings, its core insights—particularly the emphasis on relational, material, and reflective dimensions of inclusion—offer valuable guidance for early childhood education when appropriately adapted to the developmental context of younger learners.

Hackbarth and Martens conceptualize inclusion as a transformative process that goes beyond the simple integration of diverse learners. Their research demonstrates that inclusion requires a deliberate transformation of everyday classroom interactions, routines, and relationships, so that each child’s perspective and learning style are authentically recognized and valued. This transformation extends to the material and spatial dimensions of the classroom, with resources and activities intentionally designed to foster equitable participation. A distinctive feature of Hackbarth and Martens’s approach is the use of video-based documentation to reveal implicit norms and expectations, encouraging educators to reflect critically on their practices and to promote ongoing professional reflexivity (Hackbarth & Martens, 2018).

While Hackbarth and Martens’s work is not explicitly founded on the European frameworks, clear conceptual connections emerge both perspectives emphasize the need for a deep, systemic shift in educational values and practices, aligning with principles of democracy and participation.

2.3. Integrating Frameworks: Conceptual Basis

The integration of these frameworks presents a number of relevant conceptual considerations:

- The European frameworks provide the societal, ethical, and civic rationale for inclusion, outlining the competencies and goals that should underpin early childhood education.

- Hackbarth and Martens’s model supplies the practical, transformative methods necessary to realize these goals in daily educational practice.

- Their complementarity allows educators to address both the “why” (the broader democratic and sustainable imperatives) and the “how” (the concrete pedagogical transformations) of inclusion.

By uniting these perspectives, a comprehensive and nuanced foundation for inclusive early childhood education is obtained, one that is both aspirational and actionable, capable of fostering environments where every child’s right to participation, development, and belonging is authentically realized.

3. Latest research in Inclusive ECEC

Recent research on early childhood education and care (ECEC) highlights key themes including the evolving policy frameworks for inclusive education, systemic barriers affecting access and quality, and emerging empirical studies focusing on participation, pedagogical practices, and cross-sectoral approaches. This brief review focuses on these aspects to frame the current challenges and guide the present inquiry.

Research on ECEC typically oscillates between the analysis of international policy documents and global reports, and the development of empirical studies. Macchia and Torri (2023) examine national and international policy frameworks governing ECEC from an inclusive education perspective. Their analysis highlights how inclusion is increasingly framed not merely as access, but as a systemic transformation of educational environments. The study emphasizes the importance of ensuring equal learning opportunities from birth, promoting diversity, and embedding democratic values through participatory and culturally responsive practices in early education settings (Macchia & Torri, 2023).

A robust body of research confirms that high-quality ECEC underpins individual cognitive, emotional, and social development, while also enabling early detection of learning or developmental challenges (Motiejunaite, 2021). The United Nations’ Agenda for Sustainable Development 2030 frames education as a universal right. However, OECD and Council of Europe data reveal that only 27 percent of disadvantaged children in Europe participate in formal ECEC programmes, exacerbating existing gaps (Council of Europe, 2022).

The Global Report on Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE), jointly published by UNESCO and UNICEF (2024), issues an urgent call to action for governments and education systems worldwide. It highlights that the world is off track in meeting SDG Target 4.2, which aims to ensure access to quality early childhood development and pre-primary education for all children by 2030. One pressing concern is that children with disabilities are still 25% less likely to attend early education programmes, underscoring persistent barriers to access and participation. The report also reveals that only 46% of 194 countries have implemented at least one year of free and compulsory pre-primary education, limiting equitable entry points for many children. Furthermore, only 57% of pre-primary teachers in low- and middle-income countries have received adequate pedagogical training, raising concerns about the quality and inclusiveness of learning environments. Collectively, these findings point to the urgent need for systemic reforms to ensure that all children—regardless of ability or background—can benefit from high-quality, inclusive early education (UNESCO & UNICEF, 2024).

Recent scholarship shifts the focus from merely redressing inequities toward a holistic, systems-level approach that integrates health, education, and social protection—especially critical during the first 1,000 days (ages 2–5). In low- and middle-income countries, fewer than one quarter of children receive adequate early support, underscoring the need for cross-sectoral strategies and sustained investment (Draper et al., 2024).

On the empirical front, two recent contributions are particularly relevant. A Frontiers in Education Special Issue (2023) presents empirical studies on inclusion and participation in ECEC, focusing on children at risk and with disabilities, teacher self-reflection tools, socio-emotional learning programmes (such as PATHS®), and the impact of socioeconomic context on child development (Björck, 2023). Additionally, a Scoping Review by Ritosa et al. (2023) offers an exploratory overview of how children’s engagement is measured in ECEC settings, providing valuable insights into the effectiveness of inclusive practices (Ritosa et al., 2023).

These findings inform the research focus and methodological approach to assess inclusivity in Italian ECEC settings.

4. Italy’s Integrated 0–6 System and the 2025 National Curriculum Guidelines: Continuity, Innovations, and Inclusive Challenges

Italy’s integrated education system for children aged 0 to 6, formally established by Legislative Decree 65/2017, represents a significant policy innovation designed to bridge the historical divide between early childhood care (ages 0–3) and preschool education (ages 3–6). Recognizing early childhood as a foundational stage for lifelong learning and social equity, the system adopts a holistic, inclusive vision that respects and promotes the rights and needs of all children, regardless of their background or abilities. It is built upon the principles of educational continuity, accessibility, and pedagogical coherence, and is in accordance with international frameworks such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and Sustainable Development Goal 4.2 (MIUR, 2017).

The pedagogical foundation of the integrated system is articulated in the Pedagogical Guidelines for the Integrated System 0–6, which provide a systematic framework for educational planning, curriculum coherence, and the professional development of educators. These guidelines emphasize the importance of fostering meaningful learning contexts, nurturing relationships, and ensuring participation and inclusion as core dimensions of quality early childhood education (MIUR, 2021).

The most recent development in this policy area is the publication of the National Curriculum Guidelines for Early Childhood and First-Cycle Education, issued by the Italian Ministry of Education and Merit (MIM, 2025). Initially released as a draft for public consultation, the document was subsequently refined and published in its final version. The guidelines reaffirm Italy’s longstanding commitment to inclusive education, devoting a dedicated section to the notion of a “school capable of being inclusive.” They trace the historical and legislative trajectory of inclusion, emphasizing full participation and the recognition of each child’s unique potential (MIM, 2025). Notably, the document introduces inclusion as an “organisational culture,” arguing that inclusive principles should inform not only pedagogical approaches but also the structural and symbolic dimensions of educational institutions

A closer analysis, however, reveals several critical tensions. Antonacci et al (2025) pointed out some significant critical aspects. While the guidelines articulate a strong rhetorical commitment to inclusion, this is not always matched by conceptual clarity or linguistic precision. For example, the use of outdated terminology, such as describing children with disabilities as “carriers of some form of disability”, suggests a residual adherence to medical or deficit-based models. Similarly, the treatment of Special Educational Needs (SEN) appears inconsistent: the concept is frequently narrowed to socio-linguistic disadvantage, with limited consideration of broader categories such as neurodiversity or giftedness. This restrictive framing risks reinforcing dichotomies between “normal” and “special” learners, rather than advancing a universal design for learning paradigm.

Pedagogically, the guidelines at times seem to revert to a transmissive model of teaching. The recurrent use of the term Magister to describe the teacher evokes a hierarchical and directive role, at odds with contemporary understandings of educators as facilitators, co-constructors of knowledge, and relational professionals. Furthermore, the emphasis on “simple” activities and “correct” knowledge risks flattening the complexity of learning processes, limiting opportunities for exploration, creativity, and critical thinking—particularly for children whose ways of learning diverge from normative expectations (Antonacci et. al. 2025).

Nonetheless, the document contains several promising elements. The focus on the alliance between schools and families, the attention to the material and symbolic dimensions of learning environments, and the call to deconstruct exclusionary discourses reflect an awareness of the multifaceted nature of inclusion (Antonacci et. al. 2025). These elements could provide a foundation for more transformative practices, provided they are supported by clear implementation strategies and coherent professional development policies.

In conclusion, the 2025 National Guidelines continue Italy’s strong legislative tradition in support of inclusive education yet fall short of fully adhering to contemporary pedagogical research and inclusive frameworks. A more transformative policy would require not only updated terminology and broader conceptual foundations but also a reimagining of the curriculum, learning environments, and the professional identity of teachers as agents of democratic participation and co-construction from the earliest years of life.

5. Pensare IN Grande – ThinkINg Big: Investigating Inclusive Practices in Italian Early Childhood Education and Care

Italy offers a particularly fertile ground for the study of policy, practice, and inclusion in early childhood education and care (ECEC). Its long-standing commitment to inclusive schooling, coupled with recent legislative reforms establishing an integrated 0–6 education system, provides a rich and complex framework for examining how inclusive principles are enacted in diverse educational settings. Amatori and Maggiolini (2021), for instance, advance an integrated framework of care, education, and welfare in early childhood, wherein inclusion, personalization, participation, and quality are conceived as interrelated and mutually reinforcing principles. This model is underpinned by continuous professional development, effective governance structures, and a sustained focus on familial and socio-cultural contexts, including responsiveness to crisis situations such as the Covid-19 pandemic (Amatori & Maggiolini, 2021).

In a similar vein, Pensare IN Grande – ThinkINg Big is an educational project that translates these inclusive principles into research and practice. It promotes inclusive early childhood education by integrating three core dimensions: Internationality, Childhood, and Inclusion. It adopts collaborative, experiential, and intercultural approaches, emphasizing play, reflective documentation, and the critical use of technology to ensure equal opportunities for all children, including in complex or emergency contexts (Amatori et al., 2022 and 2025).

The project is a medium-term, inter-university collaborative research initiative involving four Italian universities. Data collection is managed by the Competence Centre for School Inclusion at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano. The project adopts an open and evolving framework, with continuously updated data, functioning as a longitudinal observatory. It focuses on educators working in nurseries, preschools, playgroups, and family centers, with the aim of exploring how inclusion is understood, practised, and supported across varying institutional and territorial contexts.

5.1. Research Questions and Aims

At the heart of the project are three interrelated research questions:

- To what extent do institutional frameworks influence the promotion of inclusion compared to individual pedagogical actions?

- What strategies can support an educational approach that moves beyond the mere transmission of basic knowledge to foster values, personal development, and intellectual growth?

- Which innovative approaches and strategies are effective in overcoming barriers to inclusion in diverse educational contexts?

By addressing these questions, the project aims to generate empirical insights and support the development of inclusive practices across diverse educational contexts.

5.2. Evaluating inclusion: methodological framework

A central component of the project is the systematic evaluation of inclusivity withing early childhood education environment (Amatori et al., 2022). To this end, the research team has adapted the IECE Environment Self-Reflection tool (Björck-Åkesson et al., 2017), a validated instrument designed to assess inclusive practices across eight key dimensions:

- a welcoming and friendly overall atmosphere

- an inclusive social environment

- a child-centred pedagogical approach

- a physically accessible and child-friendly setting

- the availability of materials suitable for all children

- inclusive communication strategies

- an inclusive teaching and learning environment

- a family-friendly institutional culture

The rationale behind the choice of this tool lies in its grounding in an ecosystemic perspective. As one can see, it focuses on children’s learning and play activities, as well as the relationships they experience within educational settings, placing particular emphasis on the contextual and relational factors that influence their participation. This closely adheres to the concept of inclusion detailed in this article.

The tool has been carefully adapted to reflect the specificities of the Italian educational context. The research design employs a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative data collected through a Likert-scale questionnaire with qualitative data from open-ended questions included in the same questionnaire. This integrative strategy enables the team to capture both measurable indicators of inclusivity and the lived experiences of educators. The resulting data support a comprehensive understanding of how inclusive values are interpreted and enacted in everyday pedagogical practice.

The questionnaire was developed and distributed using Qualtrics survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) through professional networks, institutional mailing lists, and educational associations, with the aim of reaching a broad cross-section of early childhood professionals across Italy. Although the questionnaire was distributed nationwide and reached early childhood professionals (0–6) working across a variety of regions and institutional setting, the analysis is based solely on the responses collected and should therefore be interpreted as representative of the sample rather than the broader population. The number of responses is not sufficient to guarantee statistical representativeness at the population level. As a result, any generalization should be made with caution, and the findings should be considered indicative rather than definitive. Nevertheless, the dataset provides a sufficiently articulated snapshot of the perspectives of those who chose to participate. In the next stages of the project, the sample will be substantially expanded, allowing to become broadly representative of the national ECEC sector.

5.3. Ethical considerations

Before beginning the questionnaire, participants were presented with clear information about the study’s aims, their voluntary participation, and their right to withdraw at any time. Consent was obtained through an online confirmation checkbox, ensuring that all responses were given knowingly and willingly.

All responses were fully anonymized, with no personal or identifying data collected. The survey platform employed SSL encryption to secure data transmission, and all data were stored on password-protected university servers in compliance with GDPR (EU 2016/679). Access was restricted to the research team, and results were reported in a way that protects participants’ identities. These procedures ensured the study was conducted with respect for participants’ rights and in line with current ethical standards.

6. Preliminary findings

6.1. Sample characteristics

The questionnaire was completed by 238 participants working in early childhood education across several Italian regions, predominantly in Trentino-Alto Adige but also in Tuscany, Liguria, Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia. The sample was largely female (96.15%), with a broad age distribution (the largest groups: 45–50 and over 55 years, both 19.11%). Most respondents were kindergarten teachers (insegnanti di scuola materna) (32.48%) or nursery educators (educatrici ed educatori di asili nido) (26.75%), with others including coordinators (20.38%), support teachers (insegnanti di sostegno) (3.82%), and various staff (14.65%). Educational backgrounds ranged from high school diploma (44.87%) to bachelor’s (14.10%) and master’s degrees (8.33%).

6.2. Quantitative results

6.2.1 Key findings at a glance

Section | Most positive (%) | 2nd positive (%) | Neutral Negative (%) |

Welcoming atmosphere | 67.0 (very welcoming) | 29.1 (welcoming) | 3.4 (neutral) |

Inclusive social context | 62.8 (strongly agree) | 32.6 (agree) | 4.6 (disagree) |

Child-centred approach | 70.4 (always) | 25.3 (often) | 4.3 (sometimes) |

Child-friendly setting | 59.2 (very suitable) | 36.5 (suitable) | 4.3 (partially suitable) |

Materials for all children | 55.7 (always) | 38.6 (often) | 5.7 (sometimes) |

Communication for all | 61.4 (always) | 33.6 (often) | 5.0 (sometimes) |

Inclusive teaching | 58.6 (strongly agree) | 37.1 (agree) | 4.3 (disagree) |

Family-friendly setting | 63.6 (very welcoming) | 32.1 (welcoming) | 4.3 (neutral) |

Table 1. Summary of quantitative results by section.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the quantitative findings. Most responses are highly positive, with most participants perceiving their settings as welcoming, inclusive, and child-centred. The highest ratings are found in the child-centred approach and welcoming atmosphere. Regarding the domain child-centred approach, most items display very high rates of positive responses, with most respondents reporting that educational practices are routinely tailored to the needs and interests of each child, and that children’s voices are listened to in daily activities. However, other items within the same domain reveal a more varied distribution: for example, when asked whether children can always freely choose activities or are actively involved in setting classroom rules, a larger portion of respondents are willing to disagree. This highlights the fact that, while core aspects of the child-centred approach are widely implemented, certain practices involving children’s autonomy and participation in decision-making remain less consistently applied. Additionally, a consistent minority (3–6% per section) reported neutral or less positive experiences, particularly with regard to materials and specific aspects of inclusive teaching, mainly those linked to the availability and quality of teacher training opportunities. This indicates that, despite a generally favorable climate, there are areas where improvement is needed.

6.2.2. Visual summary of section means scores

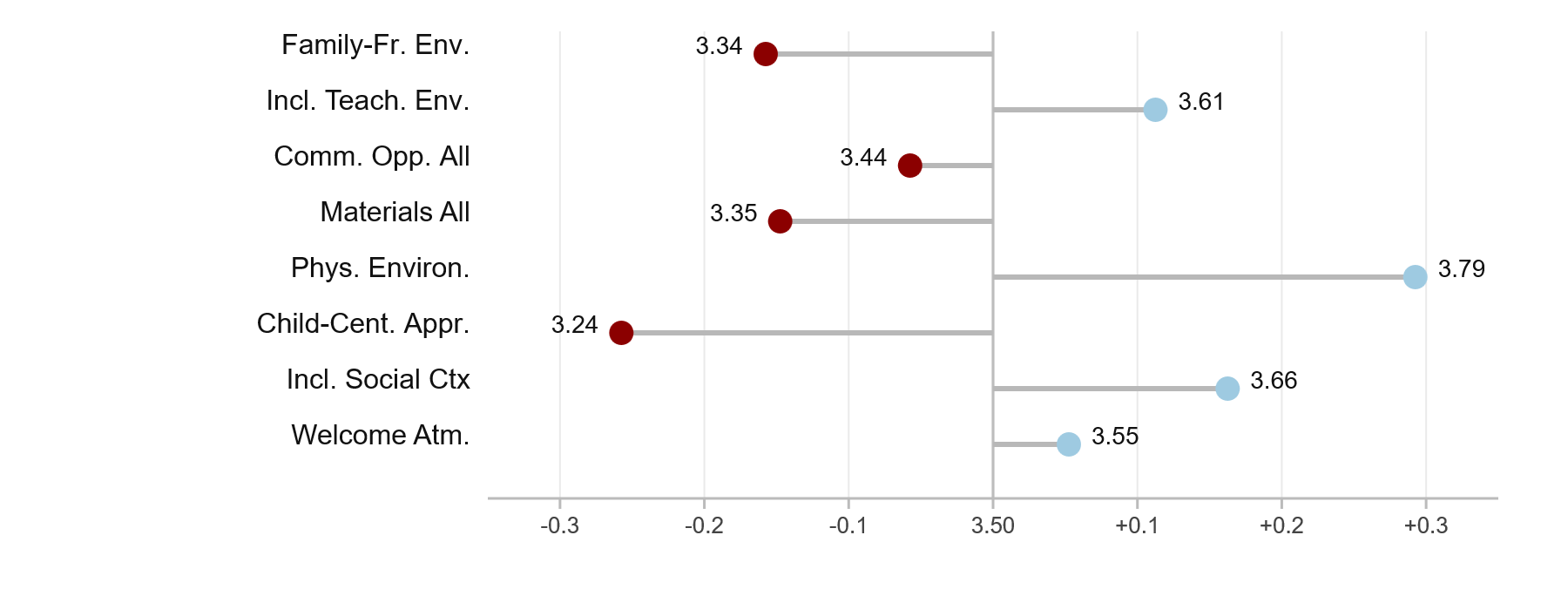

To provide an immediate and clear overview of strengths and weaknesses across the eight sections of the Pensare IN Grande/ThinINg Big questionnaire, the following deviation-from mean lollipop chart displays the mean scores for each area. Axis is centred at the grand mean (3.50); tick labels show deviations (±0.1, ±0.2, ±0.3).

Figure 1. Deviation-from-mean lollipop of section scores (grand mean = 3.50; scale 1–4). Points show section means; stems indicate deviation from the grand mean.

The chart clearly shows that the strongest aspects of inclusion, as perceived by early childhood professionals, are the welcoming atmosphere, the quality of the physical environment, and the inclusive social context, all of which score above the threshold of 3.5. In contrast, the areas of materials for all, participation and voice, professional development, and especially child-centred approach fall below this level, indicating persistent challenges in individualized planning, material adaptation, and staff training. The relatively lower mean observed for the child-centred approach in this chart reflects the discrepancies among items within the domain, with some showing very positive perception and others lower ratings, as outlined in the previous section. Overall, while the sector demonstrates a solid foundation in relational and environmental inclusion, there remain significant gaps in making practices truly responsive to every child’s needs.

6.3 Open-Ended Responses: Thematic Summary

Dimension | Strengths identifies | Challenges reported |

Welcoming atmosphere | Personalized greetings, welcome rituals | Inadequate entrance spaces, lack of quiet zones |

Inclusive social context | Emphasis on diversity, peer interaction | Group dynamics, insufficient adult-child ratios |

Child-centred approach | Tailored activities, observation-based planning | Time constraints limit full individualisation, lack of support staff |

Child-friendly setting | Child-sized furniture, safety measures | Accessibility issues, outdated facilities, limited outdoor spaces |

Materials for all children | Variety, sensory and multicultural resources | Budget limitations, lack of inclusive play materials |

Communication for all | Use of visual aids, Augmentative, Alternative Communication tools | Need for AAC training, language barriers |

Inclusive teaching | Teamwork, shared planning within the professional team | Inconsistent application, no reflective practice, poor training |

Family engagement | Regular communication, family events | Poor co-design, low participation from migrant families |

Table 2. Main themes from open-ended responses.

Table 2 synthesizes qualitative insights from open-ended responses. Practitioners frequently emphasized strong relational practices, appreciation of diversity, and collaborative teaching as key strengths. However, they also reported enduring challenges such as limited physical space, budget constraints, and insufficient training—particularly in inclusive communication and pedagogical practices. These perspectives underscore the multifaceted nature of inclusion in ECEC settings and the continuing need for targeted investment, professional development, and structural support.

7. Discussion

This preliminary analysis should be interpreted considering certain limitations, including the non-representative nature of the sample and the uneven regional distribution of respondents.

Nevertheless, the dataset offers a valuable picture of everyday inclusive practices, as it reflects the viewpoints of professionals working in diverse roles and institutional settings across several Italian regions.

Through the lens of the eight dimensions of the IECE self-reflection tool, the study highlights how each area contributes differently to the overall inclusiveness of early childhood settings. The strongest dimensions—welcoming atmosphere, inclusive social context, family-friendly culture, and accessible physical environment—confirm the presence of solid relational, organisational, and spatial foundations that support children’s sense of belonging and participation. These strengths demonstrate that democratic values are already embedded in everyday routines and that educators are committed to cultivating equitable interactions and partnerships.

At the same time, the analysis underscores several dimensions requiring more sustained attention. Materials suitable for all children and inclusive communication—particularly the use of AAC and multilingual supports—reveal gaps that directly affect children’s autonomy and participation. Similarly, the child-centred pedagogical approach and inclusive teaching practices show internal variability: while some practices are widely implemented, others—such as the co-construction of rules, the systematic promotion of children’s voice, and reflective professional decision-making—are adopted less consistently. These areas of lower performance directly inform the recommendations proposed in this article, which are illustrated in the following section.

Strengthening the weaker dimensions—especially material accessibility, communication for all, participation and voice, and reflective teaching—will be essential to translate the system’s inclusive aspirations into everyday practice. In this sense, the eight-dimensional framework functions not only as an evaluative tool, but also as a roadmap for policy and professional growth.

Moreover, these findings align with Hackbarth and Martens’s emphasis on professional reflexivity and confirm that inclusion is a dynamic process shaped by the interplay of values, practices, and institutional conditions. While the Italian 0–6 system offers a solid legislative and pedagogical foundation, its implementation requires sustained investment and coherent strategies. In this context, the “Pensare IN Grande / ThinkINg Big” project provides valuable insights into how inclusive principles are interpreted and enacted in everyday educational settings.

8. Proposed Recommendations

Building on the previous analysis, a strategic set of measures is proposed to reinforce and scale democratic engagement and transformative inclusion within Italy’s early childhood education sector:

- Targeted funding for renewing materials, adapting physical spaces, and ensuring equitable access to AAC and multilingual resources.

- Comprehensive professional development, including hands-on training in reflective practices and mentoring networks to support peer learning.

- Formalized co-design processes with families and communities, supported by language services and cultural mediation.

- Policy alignment and monitoring, through clearer inclusive terminology, adoption of universal design principles, and a mixed-methods framework to track progress and inform continuous improvement.

9. Conclusions

This study affirms the transformative potential of reflective, community‑oriented pedagogies while charting a clear agenda for action: secure dedicated resources, strengthen accredited training with reflexivity components, formalize co‑design structures with families, and adopt mixed‑methods monitoring to guide continuous improvement.

Continued data collection within the ThinkINg Big project will allow for the development of strategies capable of fostering transformative inclusion across diverse educational settings.

After expanding the sample to reach a scientifically valid level of national representativeness, the research team will be able to formulate more solid, evidence-based recommendations and practical guidelines for strengthening inclusion across the Italian 0–6 system.

By bridging the gap between aspirational vision and everyday practice, stakeholders can ensure that democratic engagement and transformative inclusion become embedded hallmarks of Italy’s early years sector.

References

Amatori, G. & Maggiolini, S. (2021). Pedagogia speciale per la prima infanzia: Politiche, famiglie, servizi. Pearson.

Amatori, G., Maggiolini, S., & Macchia (Eds.). (2021). Pensare IN Grande: L’educazione inclusiva per l’infanzia di oggi e di domani. Lecce: Pensa MultiMedia.

Antonacci, F., Antonietti, M., Di Bari, C., Granata, A., Guerra, M., Luciano, E., Mignosi, E., Sannipoli, M., Savio, D., Traverso, A., & Zizioli, E. (2025). Leggere le Nuove Indicazioni. Riflessioni e questioni intorno alla bozza 2025. Bambini, 41(4), 15–25.

Bianchi, G., Pisiotis, U., & Cabrera Giraldez, M. (2022). GreenComp: The European sustainability competence framework. https://doi.org/10.2760/13286

Björck, E. (2023). Editorial: Advancing research on inclusion and engagement in early childhood education and care (ECEC) with a special focus on children at risk and children with disabilities. Front. Educ., 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.132836

Björck-Åkesson, M., Bartolo, P. E., Kyriazopoulou, M., & Giné, C. (2017). Inclusive early childhood education environment self-reflection tool. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/inclusive-early-childhood-education-environment-self-reflection-tool

Brandolini, R. (2024). Una prospettiva inclusiva per lo 0-6.

Council of Europe (2018). Reference Framework of competences for democratic culture. Volume I. Context, concepts and model. Council of Europe Publishing.

Council of the European Union (2022). Council Recommendation of 8 December 2022 on early childhood education and care: The Barcelona targets for 2030 (2022/C 484/01; ST/14785/2022/INIT). Official Journal of the European Union, C 484, 1–12. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:C:2022:484:TOC

DLgs. 65/2017 (2017). Decreto legislativo 13 aprile 2017, n. 65. Istituzione del sistema integrato di educazione e di istruzione dalla nascita sino a sei anni. https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2017;65~art12

Draper, C. E., Tomlinson, M., Dua, T., Richter, L. M., Britto, P. R., Darmstadt, G. L., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2024). The next 1000 days: Building on early investments for the health and development of young children. The Lancet, 404, 2094–2116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01389-8

Hackbarth, A. (2017). Inklusionen und Exklusionen in aufgabenbezogenen Schülerinteraktionen. Empirische Rekonstruktionen in jahrgangsübergreifenden Lerngruppen an einer Förderschule und an einer inklusiven Grundschule. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Hackbarth, A. & Martens, M. (2018). Inklusiver (Fach-)Unterricht: Befunde – Konzeptionen – Herausforderungen. In T. Sturm & M. Wagner-Willi (Eds.). Handbuch schulische Inklusion (pp. 191–206). Opladen; Toronto: Barbara Budrich.

Macchia, V., Torri, S., Amatori, G., Maggiolini, S., & Sannipoli, M. (2025). The Pensare IN Grande / ThinkINg Big Project: A Paradigm for Democratic Education. Proceedings of the Third International Conference of the journal Scuola Democratica. Education and/for Social Justice. Vol. 1: Inequality, Inclusion, and Governance (pp. 1263–1271). Associazione “Per Scuola Democratica”.

Macchia, V. & Torri (2023). Early childhood education and care 0-6: The state of the art of the national and international regulatory framework from an inclusive perspective. Formazione & Insegnamento, 21(1), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.7346/-fei-XXI-01-23_20

MIM - Ministero dell'Istruzione e del Merito (2025). Indicazioni nazionali per il curricolo - scuola dell’infanzia e primo ciclo di istruzione. https://www.mim.gov.it/documents/20182/0/Indicazioni+nazionali+2025.pdf

MIUR - Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (2021). Linee pedagogiche per il sistema integrato "zerosei". https://www.mim.gov.it/-/linee-pedagogiche-per-il-sistema-integrato-zerosei

MIUR - Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (2021). Linee pedagogiche per il sistema integrato “zerosei”. https://www.mim.gov.it/-/linee-pedagogiche-per-il-sistema-integrato-zerosei

Motiejūnaitė, A. (2021). Access and quality of early childhood education and care in Europe: An overview of policies and current situation. IUL Research, 2(4), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.57568/iulres.v2i4.190

Ritoša, A., Åström, F., Björck, E., Marklund, L., & Sheridan, S. (2023). Measuring children’s engagement in early childhood education and care settings: A scoping literature review. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09815-4

UNESCO & UNICEF (2024). The right to a strong foundation: Global report on early childhood care and education [Global report on early childhood care and education – ECCE]. https://www.unicef.org/reports/global-report-early-childhood-care-and-education-right-strong-foundation