Learning from Pupils’ Experiences about Participatory Practices Playing a Board Game for the Development of a Learning Environment with Implications for Teacher Education

Imparare pratiche partecipative a partire dalle esperienze degli studenti coinvolti in un gioco da tavolo per lo sviluppo di un ambiente di apprendimento, con implicazioni per la formazione degli insegnanti

ABSTRACT

The EduSpace Lernwerkstatt at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano is an open learning environment for initial teacher education and further education of kindergarten and school teachers. It provides didactical materials including games for content learning and 21st century skill development. In this article we report from one part of a threefold study on the board game The Next Generation of Change Makers in which we capture pupils’ participatory experiences whilst gaming during the annual project days at school. For the evaluative research, conducted on 85 Grade 12 pupils at an upper secondary school in South Tyrol, we ran a post-game online questionnaire and combined descriptive data analysis with a thematic analysis of responses. The results can be discussed towards the opportunities for pupils to engage and improve in participatory action with the board game and allows us to draw conclusions towards the curricular concept of open learning environments in teacher education.

EduSpace Lernwerkstatt alla Libera Università di Bozen-Bolzano è un ambiente di apprendimento aperto per la formazione iniziale degli insegnanti e la formazione continua di docenti e maestri di scuola dell’infanzia. Fornisce loro materiali didattici, inclusi giochi per apprendere contenuti e sviluppo delle abilità del Ventunesimo secolo. In questo articolo riportiamo una parte di uno studio in tre parti sul gioco da tavolo The Next Generation of Change Makers, in cui cogliamo le esperienze partecipative degli studenti durante la pratica ludica in occasione delle giornate scolastiche dedicate al progetto annuale. Ai fini della ricerca valutativa, condotta su 85 studenti del quarto anno di scuola secondaria superiore dell’Alto Adige-Südtirol, abbiamo somministrato un questionario on-line post-gioco e integrato l’analisi descrittiva dei dati con l’analisi tematica delle risposte ricevute. I risultati contribuiscono alla discussione sulle opportunità per i discenti di farsi coinvolgere e migliorare l’azione partecipativa attraverso il gioco da tavolo e ci consente di trarre conclusioni sul concetto curricolare di ambienti di apprendimento aperti [open learning environments] nella formazione degli insegnanti.

KEYWORDS

Game-based learning, Participatory practices, Learning environment development, Teacher education

Apprendimento basato sul gioco, Pratiche partecipative, Sviluppo dell’ambiente d’apprendimento, Formazione degli insegnanti

AUTHORSHIP

Conceptualization (K. Kansteiner; S. Schumacher); Investigation (S. Schumacher); Methodology (S. Schumacher); Writing – original draft (S. Schumacher); Writing – review & editing (K. Kansteiner).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support for this study was provided by the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt at the Faculty of Education, Free University of Bolzano.

RECEIVED

June 6, 2025

ACCEPTED

September 15, 2025

PUBLISHED ON-LINE

September 16, 2025

1. Introduction

The EduSpace Lernwerkstatt at the Faculty of Education in Brixen-Bressanone at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano is essentially a media library for learning environments from kindergarten to secondary school. The wide range of materials on offer is intended to enable students in initial teacher education to familiarise themselves with potential didactical resources and to apply them on their teaching plans or use them in their teaching experiments (Stadler‑Altmann & Schumacher, 2020). Being a university learning laboratory bridging theory with practice, the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt is also open to experienced teachers for further training purposes and borrowing options.

Student teachers, since they are novices in teaching, are usually supported in their use of the provided materials within seminar-based and internship courses in the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt:

“The Master's programme not only aims to strengthen the subject areas but also provides more related pedagogical and didactic courses where students can test the transfer of the theoretical knowledge acquired in lectures in a practical setting. The internship starting in the first year of study serves the same purpose” (Curriculum LM-85 bis, 2017).

Another important goal is to enable student teachers to independently search for suitable teaching materials for lesson planning or preparing assignments for pupils during their practical training in kindergartens and schools (Schumacher et al., 2020).

New materials are regularly added to the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt, and the decision what to purchase, is due to various reasons: to provide a collection of good inclusive practice examples, include material recommended or requested from colleagues, which they use in their seminar teaching, and occasionally also material that serves as negative examples to be critically reflected on. Typically, these materials are demonstrated and discussed by lecturers in class or included in guided assignments. Yet, this level of reflective engagement is not ensured when student teachers approach the materials in their own during self-directed study time. Against this background, we forward the thesis that the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt should not only offer catalogued materials in the manner of a traditional media library but provide a form of scaffolding as professionalising guidance during the self-study time. To this end, we take intermediate steps by exploring how pupils use material that is at offer and determine in what respect the learning expectations are met by them. On that basis, we deduce what didactical supplement is needed. Thereof, we draw first conclusions about the possible assistance student teachers would benefit from when planning lessons self-organized in the learning environment. Our intension is to stimulate the progress of their pedagogical and didactical skills.

The study, we present, was part of a three-strand exploration of a board game with a simulation for adolescents, called The Next Generation of Game Changer, which is supposed to foster entrepreneurship (Morselli et al., 2025).As such it likewise addresses 21st century skills, which involve analysing information and arguments to make informed decisions, managing and resolving disputes in a constructive manner, valuing and respecting different perspectives, developing the ability to lead and inspire others, and making ethical decisions based on principles of justice and fairness (Cotton, 1990; Patrick, 2003). Since these skills are also incorporated in the framework of education for democratic citizenship (Brieger et al. 2024), we expected compelling participatory practices and benefits for the pupils playing the game.

In this paper, firstly, we describe the game, classify it according to the concept of pupils’ participation in school, and highlight its potential for participatory learning. Secondly, we present the research design and the results of the exploration. Thirdly, we analyse the result relating them to the specific context in which the game took place and, finally, we discuss what should be pedagogically and didactically anticipated if the game is to be played in a school context to increase its positive effects. By laying this out we nourish the idea to supplement self-driven activities in the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt and provide facilitation for novices or even experienced teachers how to prepare the game’s application and anticipate functional and non-functional actions that pupils might perform (Mian & Kansteiner, 2025).

2. Outline of the objectives and structure of the board game

The board game The Next Generation of Change Maker (NGoCM) was designed by educators and business professionals associated with the Initiative for Teaching Entrepreneurship (IFTE) for secondary schools to inspire young people to the role of future changemakers to begin their entrepreneurial ventures. Additionally, it encompasses basic personal and social topics such as responsibility and autonomy, with the stated objective of fostering solidarity in society (Lindner, 2020).

In contrast to teacher-centred methods, the game, which simulates the phases of an entrepreneurial process, includes several opportunities of participation and initiates self-driven but collaborative decision making. The first step playing the game is called Inspiration. In this initial phase, pupils are split into small groups of three to six members. To foster collaboration and simulate common functions within entrepreneurial teams each player is assigned a specific role like Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Chief Time Officer (CTO), Chief Process Officer (CPO), Chief Documentation Officer (CDO) or Chief Happiness Officer (CHO). These roles ought to help pupils to experience and understand organisational dynamics. Once they have been formed, each team selects its entrepreneurial mission (term in the instructions) by drawing a card that prompts collective brainstorming. This process prepares each group member for the second phase of Idea Generation, in which they jointly develop their mission. This can be accomplished by considering different perspectives and including the environmental and social impact of the intended project. In the third phase of Entrepreneurial Design, the teams begin to elaborate the business models developed in previous phases. The groups employ a streamlined iteration of the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010), a tool designed to facilitate the delineation of the key elements of an entrepreneurial proposal. This approach enables the groups to evaluate their concepts from various perspectives including potential customers, value propositions, suppliers, available resources, costs, and the enterprise's financial viability and sustainability. In the last phase of Final Check and Pitch, the teams prepare the concluding presentations. This is, according to the game manual, the culmination of activities because each business proposal is presented to the entire class, followed by a question-and-answer session. This session is modelled to encourage reflection on the strengths and weaknesses of each business idea.

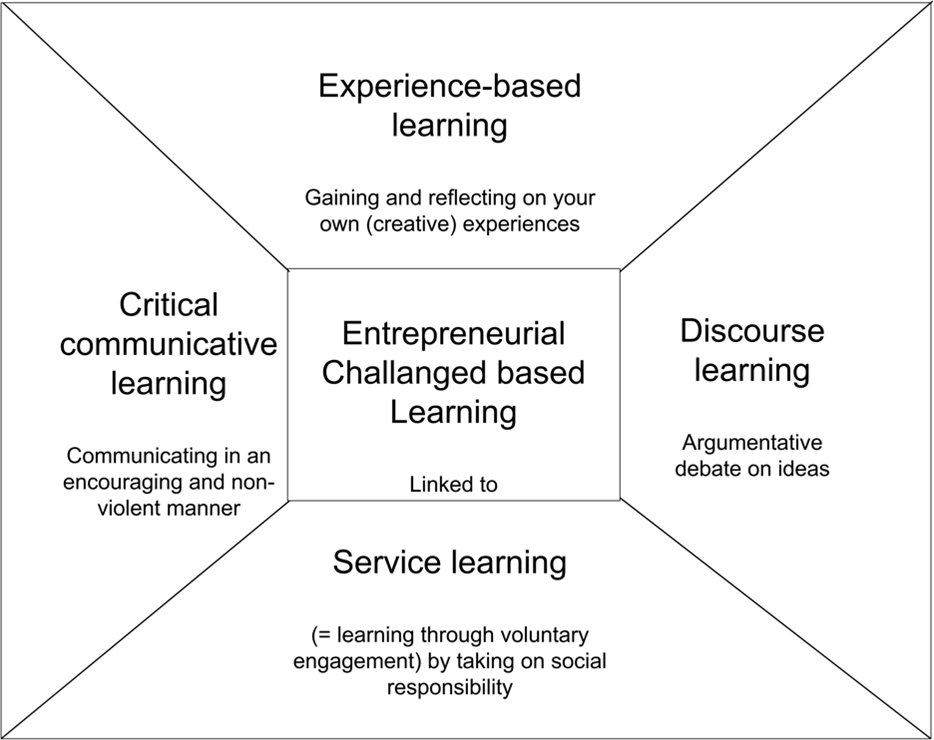

Playing the game and following these steps, pupils are expected to come across experiences that can be classified within the complex field of participatory practices associated with entrepreneurship education, such as development with a social responsibility perspective, critical (self-)reflection, dialogue and debate, as compiled by Lindner (2015) who build on various learning approaches (see Figure 1).

Figure . Learning approach for entrepreneurship education (Lindner, 2015, p. 45).

2.1. Classification of the board game

The distinction between playing and gaming is an ontological issue because it concerns structure and formalisms (Kampmann, 2019). Play can be characterised as an activity that involves the creation of imaginative scenarios and the construction of a temporary authentic world. Participants generally strive to maintain immersion in their fictional environment while playing. In contrast, games, appear as structured activities that involve interpreting and optimising objectives, rules and tactics within defined time and space limits. In the game-mode, the aim is usually to climb to the next level and follow closely the structure. Although, games and play are not the same thing, games incorporate elements of play, such as spontaneous, imaginative and self-determined action within the game's specifications. Hence, degrees of autonomy, enjoyment, creativity and role-playing are given (Staccioli, 2021).

Thanks to the play qualities in conjunction with the multifaceted rules and specifications of a game, the NGoCM format enables pupils to act independently and participate in decision-making processes in a quite comprehensive manner. In other words, the methodological structure fundamentally embodies the idea of participation (see below).

The popularity of gamification and serious games as tools for media education has grown in recent years, as they have proven effective in engaging and motivating pupils to learn (Salen, 2008; Ciziceno, 2023). To stimulate engagement with content, games must be appealing and offer an enjoyable experience (Baar, 2020). Studies consistently report that digital as well as board game-based formats not only foster knowledge acquisition but promote active participation. In addition, research by Zalewski et al. (2019) has shown that playing board games contributes to the advancement of critical skills such as problem-solving, creativity, pattern recognition, and strategic thinking, as players engage in overcoming complex challenges. These findings have recently been confirmed by a systematic review by Sousa et al. (2023), in which the authors focused on the operationalisation of various specific objectives to assess the potential of these games for learning. Their data on learning outcomes revealed considerable variability about how board games promote a diverse array of educational experiences like increasing soft skills as communication and collaboration besides the content related competences.

2.2. Ratio of participatory practices

Against the backdrop of Dewey’s educational theory (cf. Dewey, 1916), a variety of schooling arrangements and teaching methods have been discussed and evaluated that build on the idea of ‘learning by doing’ and involve pupils in democratically arranged processes and thus strengthen their skills of participation (Himmelmann, 2010; Beutel, 2021). Among the teaching methods providing such processes are projects (Gunzenreiner et al., 2024; Jormfeldt, 2023) but also real-life simulation games like prominently School as a state (https://www.schule-als-staat.eu/).

In contrast to the general idea of intentional education, in which the learning processes is determined, controllable, and reliable (see also for its critical discussion Breidenstein, 2020), these educational methods advocate an exploratory approach to learning objects that encompass the playful development of skills– and naturally unpredictable alternative courses of action.

From a theoretical point, the composite of teaching and participatory learning environment can be characterised as inherently ambivalent (Beutel, 2021). From a broader theoretical perspective, such contradictions in educational teaching have been fundamentally reflected, and six sets of contradictory demands on action in professional educational practice have been analysed (Helsper, 2004). Our example corresponds with one of them, the organisation-interaction antinomy: While academic school research has identified conditions for success and good-practice-examples of participatory learning, this is manifested against an institutional framework that includes repression, exclusion, asymmetrical and uncontrolled power, or non-transparent performance assessment (Helsper, 2004).

Participatory actions, naturally, manifest across varying levels of consequence (Mayrberger, 2012, pp. 6–7). Our study was mainly guided by this approach (each level summarised and translated by the authors):

- No participation: The learning objectives, content, working methods, and results are all predetermined. Learners behave according to instructions.

- Decoration: Learners only participate when asked to do so.

- Alibi participation: Verbal contributions from learners have no influence on the situation. Learners show voluntary, affective reactions.

- Interests and expectations: Learners are asked about their interests and expectations.

- Prepared learning environment: Learners are placed in a prepared learning situation and receive comprehensive information. They understand the project and its intended outcomes.

- Conceptualisation: Contributions from learners are recorded and conceptualised later. Learners articulate their own ideas about a learning situation.

- Participation in decision-making: The idea for a learning program comes from the teachers. Learners are involved in decision-making about e.g. methods, procedures, or assessment criteria.

- Proactive self-determination: Teachers act as supportive partners. Learners proactively and independently initiate the learning process. They are responsible for selecting content, goals, and methods.

- Complete freedom: Teachers are informed when necessary. Learners have complete freedom of choice and are responsible for regulating the social, motivational, and metacognitive aspects of their learning process.

The game, NGoCM, cannot be classified to a single category but bears the option of experiences ranging from interests and expectations up to participation in decision-making within the game’s specifications. The game aims to encourage pupils to develop an appropriate level of volatility and to engage in democratic and economic social development within the game and beyond. Once they have understood the process of entrepreneurship, a further participatory perspective emerges – that of a self-aware and responsible adult.

3. Methodology

Whereas Morselli et al. (2025) emphasise the subject-specific pupils’ outcomes with NGoCM, we were interested in the extent to which the argued strength of the simulation game meets participatory quality. With our research we intended to identify the participatory practices that pupils perform in the steps of the game. We ran a questionnaire with four items, each for one of the four phases of the game and with an ordinal-scaled Likert scale (Döring, 2023) that depicts experienced involvement in the sense of the extent of participation experience in the four game phases. To develop the scale, we drew back on Mayrberger (2012) and condensed it to a five-step gradation as shown in Table 1.

RQ 1: How much did you participate on the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th stage of the game? | |

Scale description | Definition |

1. no participation | comprises interaction level ‘no participation’: Content, methods, and results of the project are completely externally defined. |

2. by presence | comprises interaction levels ‘decoration’ and ‘alibi participation’: Learners take part in an event (e.g. panel discussion) without knowing in detail what it is about. |

3. occasionally possible | comprises interaction levels ‘interests and expectations’ and ‘prepared learning environment’: Learners articulate their own ideas about a learning situation but are not involved in the actual implementation (e.g., feedback rounds, evaluation). |

4. mostly possible | comprises interaction levels ‘conceptualisation’ and ‘Participation in decision-making’: The learning process is not initiated with but by learners and supported by teachers (in partnership) (e.g., content, objectives, methods, etc.). |

5. self-determined | comprises interaction level ‘proactive self-determination: Complete freedom of decision and responsibility for the design of learning processes for the learners (as individuals or groups) and teachers are informed if necessary. |

Table . Pentatonic Likert scale, derived from Mayrberger (2012) with condensed interaction levels.

To obtain a more profound comprehension of the underlying factors that precipitated the expressed grade of participatory involvement, in addition we collected data by two open-ended questions: RQ 2: “What did you do to fulfil your role” and RQ 3 “How could you fulfil the role better next time?” We presumed that the experience of opportunity for participation was connected to the extent one engages in the game. To analyse this data the method of qualitative content analysis as outlined by Kuckartz and Rädiker (2022), which combines deductive and inductive category development, was employed.

After we had familiarised ourselves with the data, we marked meaningful text segments related to the research questions, and defined categories and coded. Main categories were the following:

- Role-Related Actions: Specific tasks or behaviours performed to fulfil duties of the role (“I tried to motivate the others”).

- Collaborative Contributions: Interaction, communication, teamwork (“Contributed my opinion & corrected my colleagues”).

- Self-Reflection & Improvement: Ideas or reflections on how to improve role performance (“Discuss more with the group”).

- Challenges or Barriers: Difficulties or obstacles encountered in fulfilment of the role (“My role did not constitute a real task”).

- Metacognitive Awareness: Awareness about learning or group process (“I was hardly able to fulfill this role effectively”).

- Autonomous vs Supported Actions: Distinguishes between self-initiated vs externally supported actions, (“The teacher helped me to better understand the game rules”).

- Emotional/Affective Dimension: Expressions of motivation, satisfaction, or frustration, (“I felt comfortable/uncomfortable in my role”).

We got access to an appropriate field, the secondary school of Economics (WFO) in Bruneck, South Tyrol. At the WFO they prepare graduates for qualified professions in all branches of the economy (trade, commerce, industry, etc.) and in administration, as well as for professions in the digital sector that require good economic and technological skills. In October 2018 the WFO got certified as an ‘Entrepreneurship School’ and achieved the second level in 2021. Through these innovative steps and the biannual recertifications, the WFO specifically promotes a culture of maturity, personal responsibility and solidarity as part of the ‘entrepreneurial spirit’ in all areas of teaching.

We are grateful to have had the opportunity to explore the game there with 87 pupils about 17 years old, in five fourth-year classes. Playing the game was embedded into so called project days in which pupils usually get to choose what they work on (in opposite to teacher-centred lessons). In our case the pupils were kindly asked to participate in our study and thus gaming was not self-chosen. During the game, the teachers were present in the classroom and performed classroom management tasks (as recommended by Manuzzi, 2002); predominantly monitoring, disciplining, and arranging resources. The introduction was presented by a researcher.

The sampling can be regarded as a convenience sampling (Döring, 2024). The teams were randomly assembled. Despite the limitation that there was no option to run a pre-test, this setting was still satisfactory considering our interest to explore participatory experience playing the game within the educational context.

4. Results

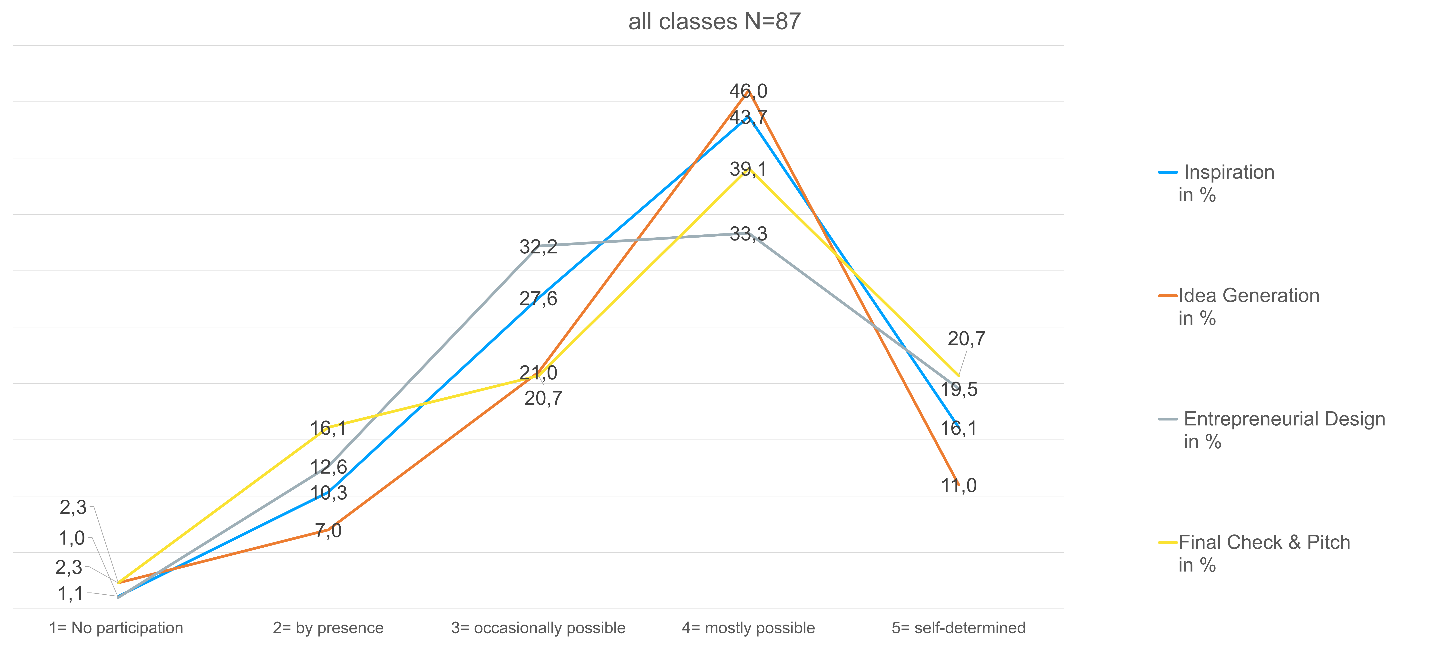

Regarding our research interest it is worth reporting the overall result of the descriptive data analysis first. According to this, the pupils’ participatory experience differs slightly comparing the stages but with a positive tendency that participation was mostly possible and even the impression of self-determination was perceived. In the first and second phase of the game (Inspiration and Idea Generation), the pupils predominantly felt that they had the opportunity to participate (N = 87, 43.7%; 46.0%), followed by the fourth phase (Final check & Pitch), which involved presenting the idea to the whole group (39.1%). The Entrepreneurial Design phase, in which the idea was to be developed using the Entrepreneurial Canvas, achieved a 33.3% approval rating. Figure 2 provides an overview.

Figure . Overall participation experience at the four game stages rated by all pupils.

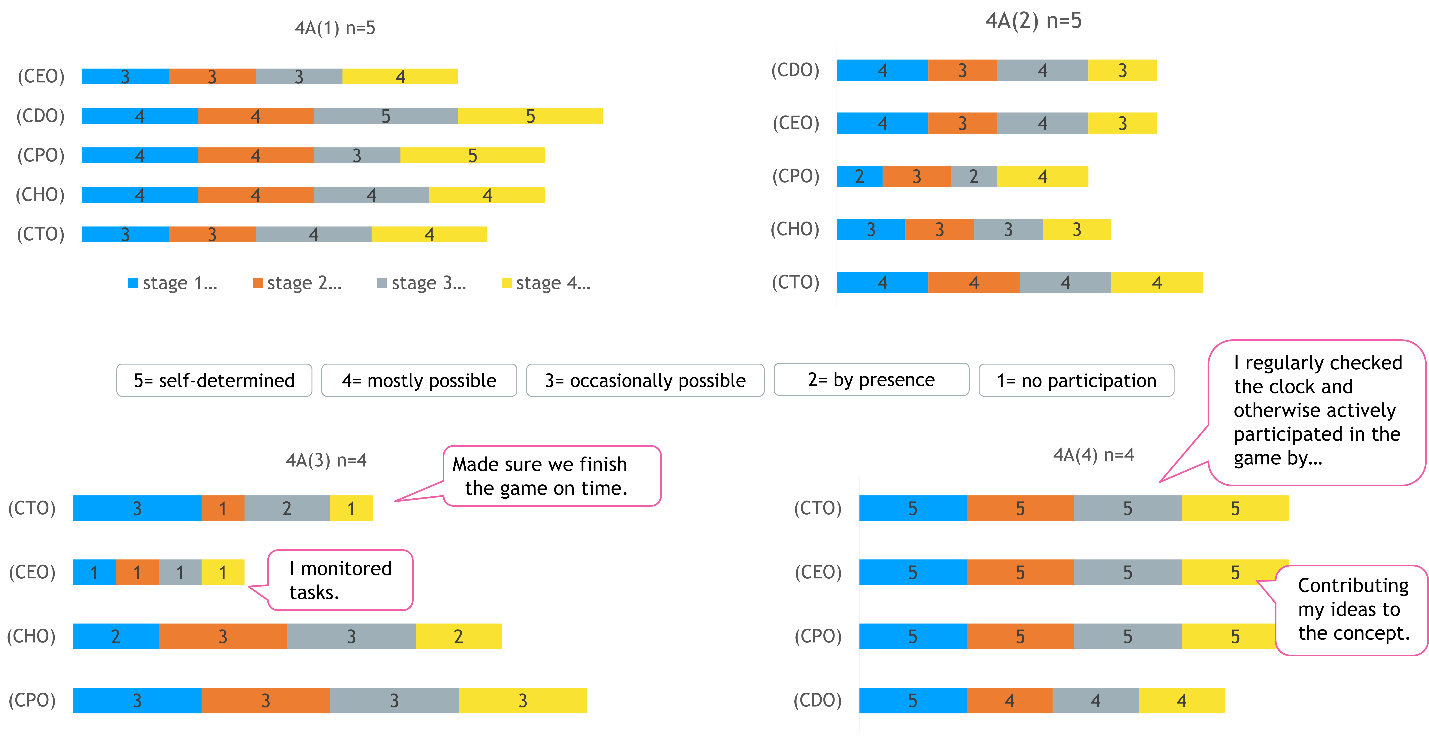

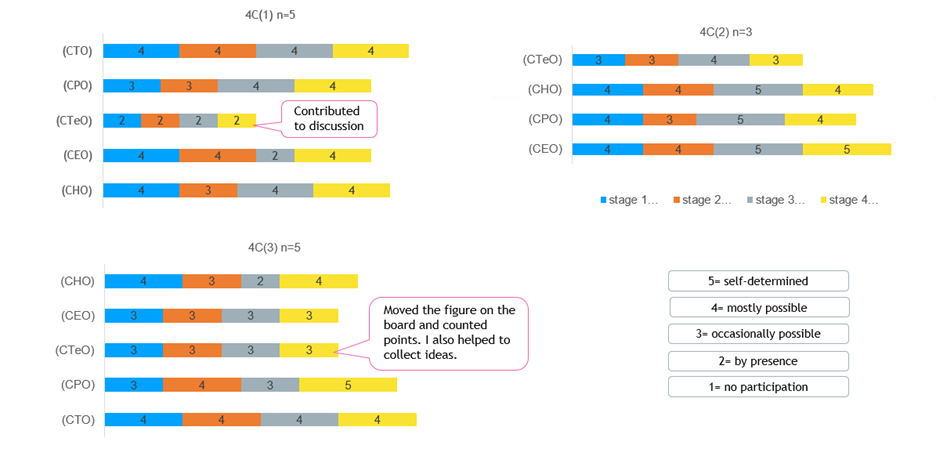

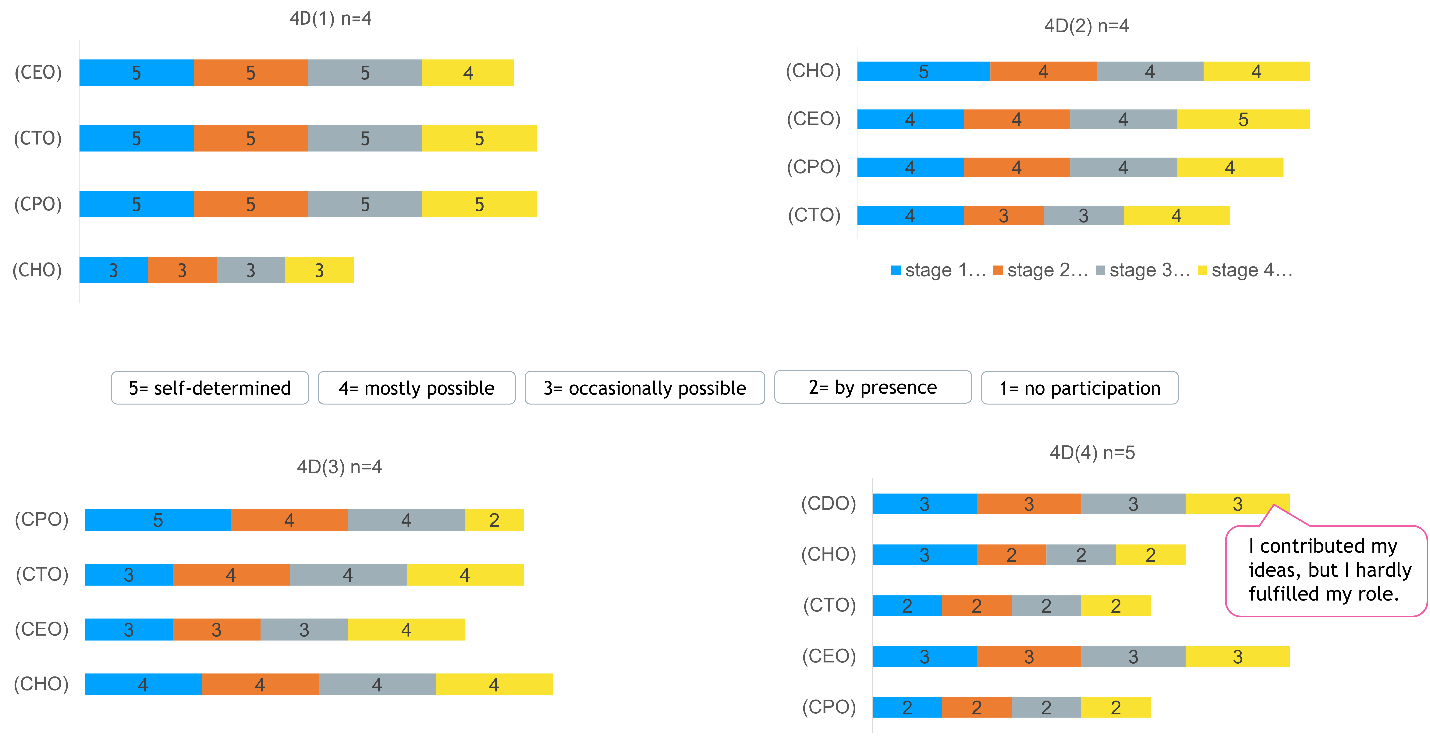

Various interaction dynamics developed in each of the teams, which can be differentiated in group-related and individual participation experiences. To examine this phenomenon, the survey results were filtered by group and role. The following graphs show the pupils’ rating according to the role they had taken in the game and the specific stage as much as for the single team in each class. In Figure 3 to Figure 7 we added examples of meaningful expressions from the written answers.

Figure . Role-specific participation experience in the four groups of Class 4A.

As you can see in Figure 3 group (4) in class 4A is characterised by the strongest self-determined participation experience shared by all group members across all stages. The 4A(4)-CTO states that, beyond his role-specific function of time management, he/she shared his ideas with the group during the game phases, as the 4A(4)-CEO also notes in the minutes. Conversely, the experience of participation in Group 3 (graph below left) is rated less favourably overall and also quite unequally. The 4A(3)-CEO assigned a low score to the opportunities for participation as he/she was mainly monitoring but likewise responded to RQ 3 which inquired after the scope of action with “Nothing”.

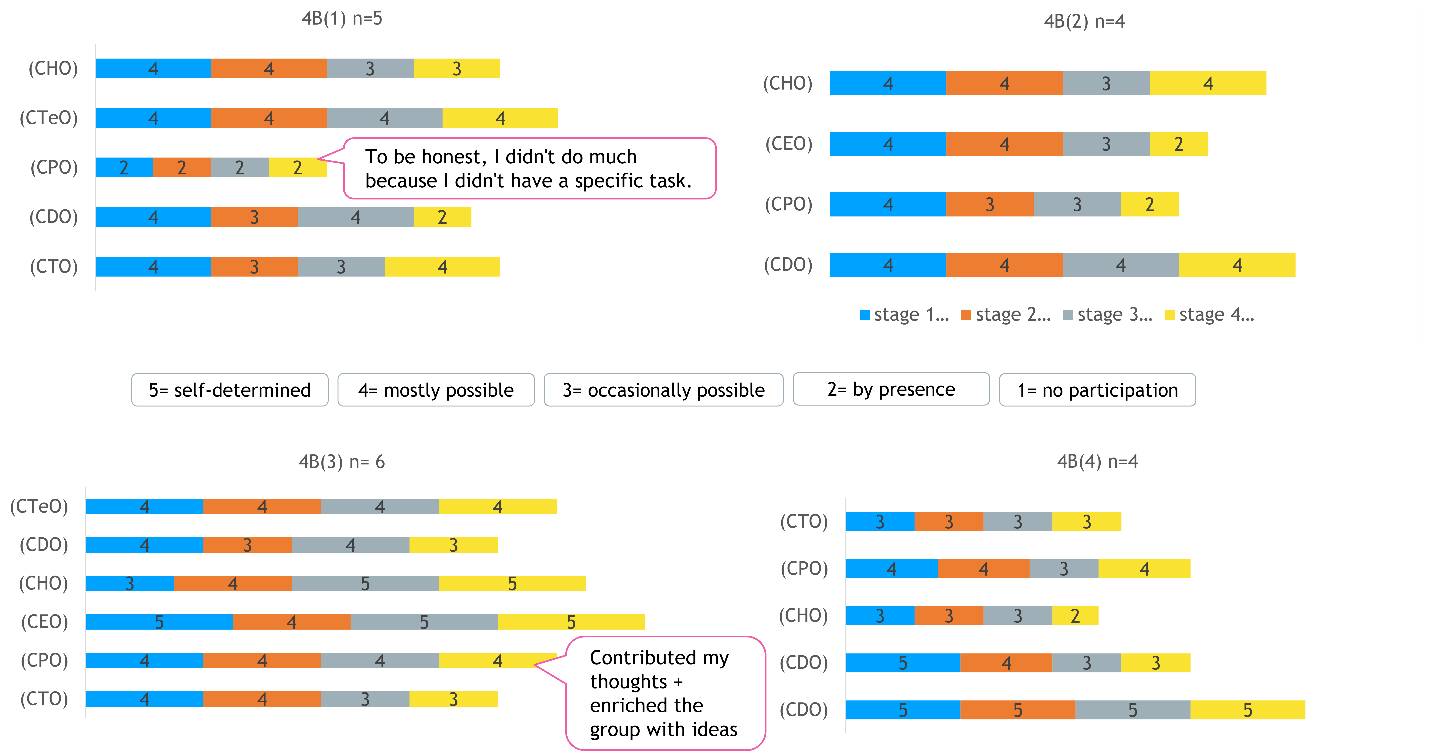

Figure . Role-specific participation experience in the four groups of Class 4B.

In class 4B, group (3) also stands out for its high level of participation across all phases calculated by mean. While the 4B(3)-CPO felt responsible for product development as well as information distribution, the 4B(1)-CPO indicated that his assigned role did not constitute a real task. This is reflected in the assessment of participation, which was rated as “by presence” in all four phases of the game as displayed in Figure 4. In response to the question regarding potential improvements for the subsequent iteration, the 4B(1)-CPO suggested a more comprehensive involvement in the project.

Figure . Role-specific participation experience in the three groups of Class 4C.

Class 4C was also divided into four groups of four, with two members of group (4) who have not completed the questionnaire, meaning that a group-based evaluation could not be carried out. The results of the ranking of subjectively experienced participation in groups (1) and (3) you can realise in Figure 5 will be considered here: While the ratings in group (3) show little variation in the participation experience across all roles, the 4C(1)-CTeO consistently experiences his role as participatory “by presence” as depicted in Figure 5. Interestingly, the field for answering questions about how 4C(1)-CTeO could improve his/her role next time was left blank.

Figure . Role-specific participation experience in the four groups of Class 4D.

As shown in Figure 6 of class 4D, group 1 is to distinguish by the fact that the CEO, CTO, and CPO all engaged in self-directed interaction throughout every phase of the game, except the 4D(1)-CEO, who only occasionally felt participation in the four phases. RQ 2 is responded to with “I tried to motivate the others” fully appropriate to the role requirements. For RQ3 4D(1)-CHO states “Contribute better inputs”. On average, group 4D(4) rated the participation experience the lowest. However, the 4D(4)-CEO and CDO slightly deviated upwards from the other experience values. In RQ2, the 4D(4)-CEO states that he/she made a note of all considerations during the process, and in RQ3 he admits that he could “discuss more with the group” next time. The 4D(4)-CDO, whose task was to record the interactions, said (answering the open-ended question) he/she was hardly able to fulfil this role effectively, but contributed by providing ideas (see Figure 6, bottom right).

Figure . Role-specific participation experience in the three groups of Class 4E.

The participation experience among the three working groups in Class 4E, which specialises in computer science and encompasses only 14 pupils, varies little as illustrates in Figure 7. The 4E(1)-CTeO rated his/her participation as ‘by attendance’ and his/her activity with the comment ‘points during interactions count’, while the 4E(2)-CTeO rated his/her opportunities for ‘participation by counting points’ as ‘occasionally possible’. 4E(2)-CTeO would like to create “nicer tables for listing the points” to better complete the role, while 4E(1)-CTeO cannot imagine how to do anything better. The participation experiences of 4E(3)-CTeO, on the other hand, are rated higher in phases 2 and 3 by “Contributed my opinion & corrected my colleagues”. In future, 4E(2)-CTeO can imagine “Contributing more opinions”.

Across the single roles and the single teams, we gain the following insights:

- Overall, we identify quite high approval towards the experience of participation during gaming, often rated between 3 to 5, which expresses that in average the pupils felt that participation was often possible.

- Due to the comparison of means of each specific role across all groups and classes we do not identify any role in which the experience of participation was clearly higher than in others (means: CDO – 3.8; CEO and CTO – 3.7; CPO – 3.5; CTeO and CHO – 3.4).

- In each class we find a team in which one role differs from the others in the perceived experience of participation. Yet, the data doesn’t allow us to relate any differences within teams to a single class.

- Finally, we noticed that the pupils, asked by open-ended questions, often didn’t give explanatory answers, and only some came up with ideas for further elaborating the role. Considering that quite some pupils explored participatory actions, fewer of them might have felt stimulated to engage in critical self-reflection. This would have been possible by viewing the quality of contributions or motivation to participate or by thinking of new strategies (e.g., active listening, asking detailed questions) and tools (e.g. set a timer, use a spreadsheet).

- In the synthesis of the responses to the open-ended questions, the concept of participation is predominantly reconceptualized as the opportunity to contribute to group discourse. Seldomly, the pupils refer to the option to handle the rules flexibly or engage in meta-level reflection on the procedural dynamics.

5. Conclusions

We differentiate the findings according to three distinct analytical perspectives, each of which informs the identified need for professional support for student teachers when operating autonomously within open learning environments that incorporate didactic games such as the one presented.

5.1. Different ways to participatory action potentials

A board game such as NGoCM offers significantly more scope for play and genuine action in a participatory sense than teacher driven lessons but probably far less than the prototyping simulating game School as a State more aspects are predetermined in terms of time and activities. In our study the pupils spend half of a school day in the classroom playing the game which could be compared to a very comprehensive group work (Johnson, Johnson & Holubek, 2005). As such it is still in differs to traditional lessons.

Despite the benefits of entrepreneurship for fostering pupils’ self-determination skills that Morselli et al. (2025) found, the contribution to the intended learning outcomes we recognize too little value for everyone (!) in the amount of time consumed. We assume that different levels of competencies among the teams and different personal interest and engagement lead to different experiences. Given that the use of the game is inherently conditional, it becomes imperative for teachers to explicitly define the pedagogical aims they intend to pursue through its application. They must also proactively anticipate which specific competencies can be effectively fostered through the game-based approach, and strategically plan the forms of facilitation required to support diverse learner profiles and team configurations in achieving meaningful progress.

5.2. Guidance is not over when the game is over

The finding that the pupils show rather superficial reflections on their behaviour in their roles and hardly name any possibilities to elaborate them could be explained by the fact that they might have felt comfortable with their role engagement and did not see the need for elaboration. Or they might have been exhausted after four hours of gaming. Anyway, this observation necessitates a critical examination of two aspects:

- The game setting supports to learn about entrepreneurship activities and to be aware of the roles within. But when it comes to the meta-reflection about the role and oneself acting in it including to find ideas to expand one’s own capacity, pupils did not engage as expected. Accordingly, some kind of instruction might be needed. This indication to guide them is supported by studies that imply that serious games (like NGoCM) are more effective when integrated into other activities (Wouters et al., 2013). Furthermore, the importance of moderation and debriefing is emphasised to ensure that the game's objectives are achieved (Crookall, 2010). The effects of game-based processes depend on a multitude of variables and on the learners' own logic. Hence, even when a game-based learning material is fully developed ready to be applied in the classroom the instructional context must be carefully designed and pedagogically facilitated to ensure alignment with educational objectives. Especially in open learning environments in which pupils organise their working processes independently, teachers must make sure that some kind of guidance is at hand (Kansteiner & Traub, 2016).

- Compared to the imaginary responsibility that most pupils took on quite well during the game the real responsibility of being involved (and needed) in an exploring research situation was not reliably fulfilled by all. We wonder whether the pupils realise the connection between their engagement in the game and their behaviour in real life and we question how much they built up a participatory self-concept for real life. We assume that it would offer an essential learning opportunity for their personality development when they were led to reflect on the dissonance of their doings and of their reflection of the doings after having played (and evaluated). That, we assume, would decisively add to building up 21st century skills.

5.3. Playing in a school context is never purposeless

When project days are carried out at school, pupils usually expect to be able to choose some interesting activity and to have a greater say in the planning and implementation of it (at least if quality characteristics are being met; Frey & Schäfer, 2007). Presenting the NGoCM game on a project day might have led the pupils to other expectations than if it had been incorporated into traditional teacher-run lessons. Furthermore, given its form as a board game with highly academic appael, the game retains a rather teaching-like character.

Unfortunately, we couldn’t inquire after the pupils’ view on how their engagement and experience of participation might have changed if they had played by their own choice or in a joyful setting out off school.

Having presented the results about participatory experiences playing a game at school we came along some promising feedback by the pupils but also identified that this was not true for all of them for several reasons. When presenting games like NGoCM in a media library like the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt it is important to address related challenges and to offer concomitant information and planning reflections, particularly for novice users. Inspired by these initial findings, we are planning further empirical studies focusing on the outcomes of selected materials implemented in school and kindergarten settings. The aim is to generate evidence that will inform the development of a facilitation concept for self-organised activities in the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt.

References

Baar, R. (2020). Spielend zur Professionalität? Der Einsatz von Spielen in der Lehrkräftebildung unter professionalisierungstheoretischer Perspektive. In U. Stadler-Altmann, S. Schumacher, E. A. Emili, & E. Dalla Torre (Eds.), Spielen, lernen, arbeiten in Lernwerkstätten: Facetten der Kooperation und Kollaboration (pp. 17–28). Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

Beutel, W. (2021). Demokratisches handeln und schule: Gründe und beispiele für Demokratiebildung. In E. Franzmann, N. Berkemeyer, & M. May (Eds.), Wie viel Verfassung braucht der Lehrberuf? (pp. 175–187). Beltz Juventa.

Breidenstein, G. (2020). Unterricht. In S. Schinkel, F. Hösel, S. M. Köhler, A. König, E. Schilling, J. Schreiber, R. Soremski, & M. Zschach (Eds.), Zeit im Lebensverlauf (pp. 299–304). transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839448625-049

Brieger, S. A., Hechavarría, D. M., & Newman, A. (2024). Entrepreneurship and democracy: A complex relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 48(5), 1285–1307. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587231221797

Ciziceno, M. (2023). From game-based learning to serious games: Some perspectives on digitally mediated learning. Media Education, 14(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.36253/me-13294

Cotton, K., & Faires Conklin, N. (1989). Research on early childhood education (School Improvement Research, Series III, 1988–1989). Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED312030

Crookall, D. (2011). Serious games, debriefing, and simulation/gaming as a discipline. Simulation & Gaming, 41, 898–920. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878110390784

Curriculum for the single-cycle Master’s Degree Programme in Education for Primary Schools (LM-85 bis). (2017). Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

Dewey, J. (1993). Demokratie und Erziehung: Eine Einleitung in die philosophische Pädagogik. Beltz. (Original work published 1930)

Döring, N. (2023). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften. Springer. (Page number removed; not included in APA reference entries for books.)

Döring, N. (2024). Stichprobe. In M. Wirtz (Ed.), Dorsch – Lexikon der Psychologie (Online-Ausgabe). Hogrefe. https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/stichprobe

Frey, K., & Schäfer, U. (2007). Die Projektmethode: Der Weg zum bildenden Tun. Beltz.

Helsper, W. (2004). Antinomien, widersprüche, paradoxien: Lehrerarbeit – ein unmögliches geschäft? Eine strukturtheoretisch-rekonstru ktive perspektive auf das lehrerhandeln. In B. Koch-Priewe, F. U. Kolbe, & J. Wildt (Eds.), Grundlagenforschung und mikrodidaktische Reformansätze zur Lehrerbildung (pp. 49–99). Klinkhardt.

Himmelmann, G. (2010). Brückenschlag zwischen Demokratiepädagogik, Demokratie-Lernen und politischer Bildung. In D. Lange & G. Himmelmann (Eds.), Demokratiedidaktik (pp. 19–30). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-92534-9_2

Gunzenreiner, J., Reitinger, J., & Rombach, M. (2024). Relevanz von demokratielernen und partizipation im kontext von schule und unterricht. In J. K. Franz, J. Langhof, J. Simon, & E. K. Franz (Eds.), Demokratie und Partizipation in Hochschullernwerkstätten (pp. 148–161). Klinkhardt.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Holubek, E. (2005). Kooperatives Lernen – kooperative Schule. Verlag an der Ruhr.

Jormfeldt, J. (2023). Experiences of school democracy connected to the role of the democratic citizen in the future: A comparison of Swedish male and female upper secondary school students. Journal of Social Science Education, 22(3), 6008. https://doi.org/10.11576/jsse-5530

Kampmann, W. B., & Juel Larsen, L. (2019). The ontology of gameplay: Toward a new theory. Games and Culture, 15(6), 609–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019825929

Kansteiner, K., & Traub, S. (2016). Umgang mit vielfalt als herausforderung für offene unterrichtsformen und darauf bezogene kompetenzentwicklung von lehrkräften. In G. Lang-Wojtasik, K. Kansteiner, & J. Stratmann (Eds.), Gemeinschaftsschule als pädagogische und gesellschaftliche Herausforderung (pp. 125–141). Waxmann.

Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung (5th rev. ed.). Beltz Juventa. (Page range removed; not included for monographs.)

Lindner, J. (2020). Entrepreneurship education by Youth Start—Entrepreneurial challenge-based learning. In The challenges of the digital transformation in education: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL2018) – Volume 1 (pp. 866–875). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11932-4

Manuzzi, P. (2002). Pedagogia del gioco e dell’animazione: Riflessioni teoriche e tracce operative. Guerini Studio.

Mayrberger, K. (2012). Participatory learning: Designing with the social web. On the contradiction of prescribed participation. MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis der Medienbildung, 21, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/21/2012.01.12.X

Mian, S., & Kansteiner, K. (2025). The potential of phenomenological vignettes to discover play experiences in a game with perspectives on teacher education and EduSpace Lernwerkstatt. Formazione & Insegnamento, 23, Article 8086. https://ojs.pensamultimedia.it/index.php/siref/article/view/8086

Morselli, D., Mian, S., Schumacher, S., & Andreatti, G. (2025). The next generation of change makers: Developing an entrepreneurship competence in VET students through a board game from the EduSpace Lernwerkstatt. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference of the journal “Scuola democratica”: Education and/for social justice. Vol. 2: Cultures, practices, and change (pp. 72–84). Associazione per Scuola Democratica. Retrieved September 4, 2025, from https://hdl.handle.net/10863/46547

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Wiley. Retrieved September 4, 2025, from https://cimne.com/cvdata/cntr2/spc2390/dtos/dcs/businessmodelgenerationpreview.pdf

Patrick, J. J. (2003). Essential elements of education for democracy: What are they and why should they be at the core of the curriculum in schools? [Conference presentation]. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved September 4, 2025, https://www.civiced.org/pdfs/EEOEforDemocracy.pdf

Salen, K. (Ed.). (2008). The ecology of games: Connecting youth, games, and learning. MIT Press.

Schumacher, S., Stadler-Altmann, U. M., & Riedmann, B. (2020). Verflechtungen von pädagogischer theorie und praxis: EduSpace Lernwerkstatt: Stationär und mobil. In U. Stadler-Altmann, S. Schumacher, E. A. Emili, & E. Dalla Torre (Eds.), Spielen, lernen, arbeiten in Lernwerkstätten: Facetten der Kooperation und Kollaboration (pp. 184–193). Klinkhardt. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:18432

Staccioli, G. (2008). Il gioco e il giocare: Elementi di didattica ludica (4th ed.). Carocci.

Sousa, C., Rye, S., Sousa, M., Torres, P. J., Perim, C., Mansuklal, S. A., & Ennami, F. (2023). Playing at the school table: Systematic literature review of board, tabletop, and other analog game-based learning approaches. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, Article 1160591. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1160591

Stadler-Altmann, U. M., & Schumacher, S. (2020). Spielen, lernen, arbeiten in Lernwerkstätten: Formen der Kooperation und Kollaboration. In U. Stadler-Altmann, S. Schumacher, E. A. Emili, & E. Dalla Torre (Eds.), Spielen, lernen, arbeiten in Lernwerkstätten: Facetten der Kooperation und Kollaboration (pp. 11–16). Klinkhardt. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:18432

Wouters, P., van Nimwegen, C., van Oostendorp, H., & van der Spek, E. D. (2013). A meta-analysis of the cognitive and motivational effects of serious games. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031311

Zalewski, J., Ganzha, M., & Paprzycki, M. (2019). Recommender system for board games. In 2019 23rd International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC) (pp. 249–254). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSTCC.2019.8885455