Enhancing plurilingual awareness in the Italian class: A pedagogical proposal

Promuovere la consapevolezza plurilingue nella classe di italiano: Una proposta pedagogica

Silvia Scolaro

Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Culturali Comparati, Università Ca’ Foscari, (Venice, Italy) – silvia.scolaro@unive.it

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3119-4704

ABSTRACT

The present work analyses a field trial experiment done during an intensive summer FL/L2 Italian course. It was divided into three phases. In the first one, learners drew their linguistic biography. Then, they were asked to read a text about how a non-native Italian author describes her approach to the Italian language and, in a similar fashion, narrate their own encounter with Italian language and what it represented for them. Finally, students composed a multilingual poem. This approach uses art-based techniques to improve the expressive means of learners by fostering awareness of their linguistic heritage. These activities were designed to be diverse and multimodal to support and promote the centrality of students while stimulating the use of language in a cognitive reflexive way.

Il presente lavoro analizza un esperimento sul campo condotto durante un corso intensivo estivo di italiano come LS/L2. L’esperimento è stato diviso in tre fasi. Nella prima, gli studenti hanno disegnato la propria biografia linguistica. Successivamente, è stato chiesto loro di leggere un testo in cui un’autrice non madrelingua italiana descrive il suo approccio alla lingua italiana e, in modo simile, di narrare il proprio incontro con la lingua italiana e ciò che aveva rappresentato per loro. Infine, gli studenti hanno composto una poesia multilingue. Questo approccio utilizza tecniche basate sull’arte con l’obiettivo di ampliare i mezzi espressivi degli studenti, favorendo la consapevolezza del loro patrimonio linguistico. Queste attività sono state intenzionalmente concepite per essere diversificate e multimodali, supportando e promuovendo la centralità dello studente e stimolando l’uso della lingua in modo riflessivo e cognitivo.

KEYWORDS

Italian language learning and teaching, Art-based approaches, Plurilingualism, Second language acquisition, Translanguaging

Apprendimento e insegnamento della lingua italiana, Approcci basati sull’arte, Plurilinguismo, Acquisizione della seconda lingua, Translanguaging

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The Author declares no conflicts of interest

RECEIVED

October 30, 2024

ACCEPTED

December 20, 2024

PUBLISHED

December 31, 2024

1. Introduction

A language is a system that allows us to interact with the world by expressing ourselves. When we learn a new language, the new language system encounters and intertwines with the other language(s) we already know (Canagarajah, 2011). Would metacognitive thinking help promote language students’ awareness of their plurilingual selves?

In its Companion Volume with New Descriptors (CoE, 2018, pp. 28–29, 159–164), which supplements the Common European Framework of Reference for languages through another Companion Volume (CoE, 2020, pp. 30, 123–128), the Council of Europe underlines once again the importance of cultivating multilingualism (i.e., the presence of multiple languages in society) as well as plurilingualism (i.e., the dynamic presence of multiple language repertoires in an individual). This reiterates an already-existing conceptual trend, which is mirrored in earlier foundational documents (CEFR, 2001, chapter 8).

On a more practical and pedagogical level, Europe fosters language learning and teaching mainly through plurilingual approaches (Candelier, 2003; Candelier & De Pietro, 2012). In this sense, key CoE documents are: the Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education (Beacco et al., 2016), and the Framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and cultures (acronym: FREPA/CARAP; Council of Europe, 2010), which is available on the website of the European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML).

Regarding the development of plurilingual competence, the Companion Volume lists the following abilities:

- Switch from one language or dialect (or variety) to another.

- Express oneself in one language (or dialect, or variety) and understand a person speaking another.

- Call upon the knowledge of a number of languages (or dialects, or varieties) to make sense of a text.

- Recognise words from a common international store in a new guise.

- Mediate between individuals with no common language (or dialect, or variety), even if possessing only a slight knowledge oneself.

- Bring the whole of one’s linguistic equipment into play, experimenting with alternative forms of expression.

- Exploit paralinguistics (mime, gesture, facial expression, etc.) (CoE, 2020, p. 30).

The pedagogical intervention presented in this work leverages these competences, and more specifically, the sixth one: the ability to use one’s own whole linguistic repertoire experimenting with new forms of expression.

In nowadays’ Italy, almost 10% of students in primary and secondary schools have a migratory background (MIM, 2020). In such a context, the development of the plurilinguistic educational practices is favoured by current legislation and by some pedagogical projects that target area that host an elevated number of pupils with migratory background (Carbonara & Scibetta, 2018; Della Putta & Sordella, 2022). However, despite that, it is undeniable that most schooling in Italy can still be considered monolingual (Bagna, Machetti & Barni, 2018).

It comes as no surprise, then, that the plethora of Italian courses for foreigners—even those at the university level—abide by the same monolingual paradigm (Block, 2003 & 2014; Cook, 1996; Ortega, 2014). Despite the spread of ideas and principles that aim to develop competences linked to plurilingualism—and in spite of our everyday multilingual reality—the monolingual paradigm endures to date, positing one language equals one culture (Maher, 2017; Vallejo & Dooly, 2019). And yet Italian language classes for foreigners are plurilingual and pluricultural.

Beside monolingualism, another bias is present, which Block (2014) calls the “linguistic bias”—that is, “the tendency to conceive of communicative practice exclusively in terms of the linguistic (morphology, syntax, phonology, lexis) although the linguistic dimension is often complemented with a consideration of pragmatics, interculturalism and learning strategies”. To this, a well-known fact about second language acquisition could be added: successful learners are not the ones who have a well-developed morpho-syntactic and lexical competence, but those who can use the language in a pragmatically and socially correct way—according to the situation where interaction takes place (Nuzzo & Santoro, 2017; Nuzzo, 2019). Therefore, Block (2014) recommends active involvement with both embodiment (Bourdieu, 1990 & 1991) and multimodality as a way, based on semiotics, to observe what people do when they interact with each other. In fact, individuals do not communicate only ‘linguistically’ (Norris, 2004; Jewett, 2009; Kress, 2009). Furthermore, as observed by Busch,

“the linguistic repertoire develops and changes throughout life in response to needs and challenges we are confronted with and […] emotionally lived experiences of singular or repeated interactions with others—whether they are evaluated as positive or as negative—play a central role in the process of embodiment” (Busch, 2015, p. 10).

As Blommaert states: “The fact is, however, that someone’s linguistic repertoire reflects a life, and not just birth, and it is a life that is lived in a real sociocultural, historical and political space” (Blommaert, 2008, p. 17).

These considerations motivate the research questions of this case-study: why not try to avail the plurilingual competences of participants in an Italian language course provided by an Italian university? Could this practice be a useful tool for enhancing Italian language learning?

2. Theoretical underpinnings

After introducing the general context concerning the European and Italian policies on multilingualism and plurilingualism, this paragraph will introduce the main theoretical underpinnings that guided the case-study which, will be fully described in the next section.

2.1. Translanguaging

First of all, what is ‘translanguaging’? The Companion Volume defines it in the following way:

“By a curious coincidence, 1996 […] was also the year in which the term ‘translanguaging’ was first recorded (in relation to bilingual teaching in Wales). Translanguaging is an action undertaken by plurilingual persons, where more than one language may be involved. A host of similar expressions now exist, but all are encompassed by the term plurilingualism” (CoE, 2020, p. 31)

Canagarajah had previously outlined it as:

“A neologism, it has come to stand for assumptions such as the following: that, for multilinguals, languages are part of a repertoire that is accessed for their communicative purposes; languages are not discrete and separated, but form an integrated system for them; multilingual competence emerges out of local practices where multiple languages are negotiated for communication; competence doesn’t consist of separate competencies for each language, but a multicompetence that functions symbiotically for the different languages in one’s repertoire; and, for these reasons, proficiency for multilinguals is focused on repertoire building – i.e., developing abilities in the different functions served by different languages – rather than total mastery of each and every language” (Canagarajah, 2011, p. 1).

In 2014, García and Li Wei further developed the concept of translanguaging through a complex theory that frames it as both a social and pedagogical practice. It can serve as a tool for research in both sociolinguistics and applied linguistics and, at the same time, as a method for linguistic education, allowing deeper reflection on known languages, their varieties, and their use in social and communicative activities. The authors describe translanguaging pedagogical practices as promoting integrated approaches that draw on the learners’ entire linguistic repertoire, focusing on creative elements that enable learners to reflect metacognitively on the concept of ‘languaging’ (Jasper & Madsen, 2016 and 2018), understood as a complex and fluid practice. In this sense, the different languages (or varieties or dialects) known by the learners are acknowledged and validated, contributing to the co-construction of individual identity in relation to their environment and past experiences. In this case study, translanguaging has been used as a means to valorise the individual, their languages, and their potential in constructing the identity of the complex self (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011; Mercer, 2011) in relation to the complexity of society across space and time (Morin, 2017; inter alia).

2.2. Visual linguistic autobiographies

Introspective tools, such as diaries, logbooks, self-narratives, and similar tools (Dörnyei, 2007, pp. 156–159; Mackey & Gass, 2016, pp. 228–230), are commonly used in qualitative linguistics research as instruments for researchers to obtain “hidden” information. At the same time, they help learners reflect on their language learning process. Pavlenko (2007, p. 165) defines these tools as “the first source of information about learners’ beliefs and feelings.” While this type of tool can illuminate information that would otherwise be unattainable, it also carries two biases that cannot be ignored: first, authors select the information they wish to share, and second, their products are subject to the researcher’s interpretation (Franceschini, 2006).

An introspective tool often used in qualitative sociolinguistics research is the linguistic biography. It may take discursive, written, aural, or visual forms. Even the Council of Europe (CoE) supports its use through the European Language Portfolio (ELP), which consists of three parts: the linguistic passport, the linguistic biography, and the dossier. The “Intercultural Encounters Autobiography” is also included.

The linguistic biography is thus regarded as a valid (self-)reflective narrative instrument, closely tied to emotion, that enhances the author’s awareness of their linguistic plurality, which is closely linked to their sense of identity.

“The schematization and comparison of the various temporal dimensions of the story, in particular between that of physical or subjective time (“Events”) and that of biographical-linguistic time (“Languages”), make it possible to make visible, even graphically, the self-reflective potential of AL with respect to a more generic life story” (Cognini, 2020, p. 411; translated by the Author).

In applied linguistic research, the field of autobiographical narratives for both language learners and teachers has been expanding in recent years to include other forms and modalities in addition to written and spoken forms. Studies now involve autobiographies narrated through drawings or photographs (Nikula & Pitkänen-Huhta, 2008) or multimodal formats where writing, images, and sounds combine (Menezes, 2008). More frequently used examples include silhouettes or self-portraits, which are used as tools for linguistic autobiographies with both learners and student-teachers (Cognini, 2020; Kalaja, Alanen, & Dufva, 2008, 2011; Melo-Pfeifer, 2021; Muller, 2022; inter alia).

For this case study, visual linguistic autobiographies were chosen. As a narrative typology, they can be considered “made,” as defined by Riessman (2008), since they were created by the learners in a specific context for a defined purpose, at the teacher’s request.

According to Molinié (2015, p. 450):

“Reflective drawing is an apparatus comprising the transmission of an instruction, the making of a drawing (by a child, a teenager or an adult), and an exploratory discussion of the drawing (between the drawer and the practitioner/researcher or between peers). This methodology: 1) makes visible and acknowledges sociolinguistic determinants and their movement in the environment in which the player lives; 2) leads to processes of verbalization, sharing and awareness-raising of these patterns and determinants; 3) facilitates re-mediation and the production of new representations; 4) increases social mobility as an open, dynamic, complex, unstable and unpredictable process” (Molinié, 2015, p. 450).

Moreover, when analysing the visual narratives it is important to value not only the images but also the relationships between them, to understand how the different components of the product interact one with another (Busch, 2006). The conceptual structure and the interaction among the constituents are described and successively semiotically interpreted. Notwithstanding the above mentioned biases that this tool holds, the adoption of instruments such as the visual autobiography allows data gathering in an alternative way and can provide the research with an additional dimension.

2.3. Art-based approach: plurilingual poetry

Recently, in the field of applied linguistics, researchers have developed new tools to investigate multilingually, enabling studies across languages or involving multilingual data (Holmes et al., 2016). Among these are the so-called ‘art-based approaches,’ which leverage embodiment and expressive multimodality inherent in humans and form part of the aesthetic paradigm in plurilingual education (Dompmartin-Normand & Thamin, 2018; Kalaja & Melo-Pfifer, 2019; Moore et al., 2022).

In the qualitative research based on these approaches the need “to extend beyond the limiting constraints of discursive communication in order to express meanings that otherwise would be ineffable” (Barone & Eisner, 2012, p. 1) is felt. This is further explained by Merriam and Tisdell:

“Most qualitative researchers analyse data that are words. But people do not make meaning or express it only through words; they also do so by art, in visual art, in symbols, in theatre-based art, and through photography, music, dance, story-telling, or poetry. Since the advent of the new millennium, there has been much more of an emphasis on how creative expression can be a part of qualitative research efforts in what has come to be referred to as Arts Based Research (ABR)” (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016, p. 65).

Research based on art can be seen as a new, more holistic, way to be taken into consideration in order to possibly overcome the monolingualism and the monolinguistic biases, shedding light on those aspects that word-based data, typically used in qualitative research, prevents from emerging (Butler-Kisber, 2010).

Linking to what has been discussed in the previous paragraphs, ABR comprises three main characteristics:

- It favours the emotional link that undergoes cognition.

- It can facilitate those learners yet to master the linguistic means to express themselves through writing in the target language, i.e., illiterates or immigrants of recent arrival, etc.

- It engages the subject in (self-)reflection on the process which undergoes language learning through the means of alternative narrative ways compared to writing or oral stories.

On this topic Ortega says:

“Human meaning-making is always multisensory and embodied, multimodal and situated, and always involving much more than purely linguistic resources or perfect correspondences between what is said (a linguistic matter of words but also embedded in many other nonlinguistic signs, symbols, and resources), what is meant (a nonlinguistic matter of intention and construal), and what is understood (a nonlinguistic matter of construal and effect)” Ortega (2019, p. 29).

In this project, plurilingual poetry (PP) was used—a type of poetry that draws on the writer’s diverse linguistic and semiotic resources (García & Li Wei, 2014).

Composing plurilingual poetry can be considered as a way to express the self as whole through the different languages known by the author. This type of poetry has also been defined as a type of ‘identity text’ (Cummins & Early, 2011), i.e., an instructional choice that showcases students’ literacy expertise and supports literacy engagement by affirming the cultural and linguistic resources that minoritized immigrant students bring to their learning. Identity texts are creative academic projects in which students invest their identities by drawing on the full range of their cultural and linguistic repertoires. These projects are then said to function as mirrors to reflect students’ identities back to them in a positive light. As students then share their identity texts with broad audiences, they receive positive affirmation of their cultural, linguistic and social identities (Prasad, 2018, online).

Poetry allows authors to ‘play’ with languages, interacting with them not only phonologically but also semiotically in an aesthetic manner. In multilingual classrooms, where learners may not share the same languages (or varieties or dialects), it creates intersubjective ‘spaces of void’ for interpretation (Prendergast, 2009).

In recent decades, poetic inquiry—the use of poetry to produce, collect, analyse, or explore data—has gained prominence as a powerful discovery tool. It reveals connections and subtleties often overlooked by conventional research methods (Kubokawa, 2023). As an effective reflexive or self-study technique, poetic form articulates the tensions and complexities of lived experience. It challenges our engrained modes of thinking and expression as it breaks from the confines of linear ways of knowing. (Mandrona, 2015, p. 107)

3. Methodology

In order to provide a thorough response to the research topic, the methodology employed a range of qualitative tools in addition to quantitative data analysis techniques. The following section will describe the context and the participants, then it will examine the tasks used, the data collected and its analysis.

3.1. Context and participants

This case study was conducted during a summer intensive online Italian language course organised by an Italian university. The course was 70 hours long and lasted five weeks; classes were held from Monday to Friday, for 3.5 hours every day. The students attending the course were 21 adults with different countries of origin: Afghanistan, Bolivia, France, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Russia, Turkey, Iran, Ukraine and the U.S.A. Some were students in their home countries, others were international university students, while others were studying Italian for work or personal reasons. At the time the course was offered, some participants were residents in Italy, while others attended the course from their home countries. The level of the course was B1 according to the CEFR. Twelve out of the 21 students participated in all the three tasks proposed and of these six gave their informed consent to be part of the research. For this reason, only the products and the data gathered from these six participants will be discussed in this paper.

The aim of this study was to determine whether pedagogical activities fostering (self-)reflection and metacognition on known languages (or varieties or dialects) and their aesthetic use could enhance awareness of processes and strategies for learning Italian.

This was done in three phases, each one administered in the form of a task (Long, 1985 e 2005; Willis & Willis, 1996; Skehan, 1998; Ellis R., 2000, 2003 and 2009; Diadori et al., 2009; inter alia). Participation in the tasks was voluntary. At the end of the course a questionnaire was also used to gather further information on the students’ perceptions concerning the activities done during the course.

3.2. Tasks

In the following section the tasks given will be briefly described.

3.2.1. First task

The first task required the learners to upload their visual autobiography to a shared Padlet. The task was explained by the instructor during class, and examples were shown. The students were informed that the main topic of the visual autobiography was their encounter with the languages (or varieties or dialects) they knew: they were asked to visually depict when, where, and with whom they came into contact with these languages. In essence, they were asked to illustrate their ‘spatial repertoire,’ which “links the repertoires formed through individual life trajectories to the available linguistic resources in particular places” (Pennycook & Otsuji, 2014, p. 166). The Padlet where the autobiographies were posted was shared among the class so everyone could view them. Nonetheless, during class time, learners were given the opportunity to verbally share and narrate their visual autobiographies. Since some of the drawings depicted scenes of war or other significant calamities and suffering, the teacher, prioritising the well-being of the learners (Menegale, 2022), deliberately chose to make the oral narration of the biography optional, leaving it to those who voluntarily wished to share their life experiences. The objective of this first task was to foster awareness of the plurilingual self, focusing on how and when we encounter languages and how we learn or acquire them. The task emphasises the learning of additional languages as subjectively experienced by the students (Kalaja & Pitkänen-Huhta, 2020).

3.2.2. Second task

The second task required reading a passage from the book In altre parole [In Other Words] by the non-native Italian writer Jhumpa Lahiri and reflecting on her approach to the Italian language, summarised in a written composition. This was a deliberate choice made by the instructor. In the first few pages of the book, the author describes her approach to the Italian language as different from her L1s in a poetic and visual way. The aim was to enhance students’ awareness of how and why they chose to study the Italian language. The compositions submitted by the learners were later analysed using the qualitative analysis software MAXQDA for thematic analysis.

3.2.3. Third task

The third task involved producing plurilingual poetry on the topic ‘I and My Languages.’ The purpose was, once again, for the students to recognise their multilingualism as a personal resource, enabling them to use different languages to express ‘the self.’ No additional rules or constraints were imposed; learners were free to compose their poetry, drawing on their linguistic resources in any way they preferred.

The aim of these three tasks was explained to students only at the end of the course. This was done to avoid influencing learners and their performances, thereby minimising the Hawthorne effect. In the final stage, participants were also asked to complete an online questionnaire about their perceptions of the activities proposed during the course.

4. Analysis

This paragraph will present the analysis of the above-mentioned products.

4.1. Analysis of the visual language biographies

All six biographies depict the concept of a path, illustrated through lines connecting space and time, from the authors’ birth to the present. Three of them follow a spiral structure, one moves from top to bottom, another from bottom to top, and one takes a zig-zag trajectory. All include the concept of family or home, where the mother tongue was learned, followed by formal education in language learning, and later, languages tied to personal choices: passions, current or future studies, or aspirations for self-recognition or better job opportunities. Some language choices are constrained by external circumstances, such as war.

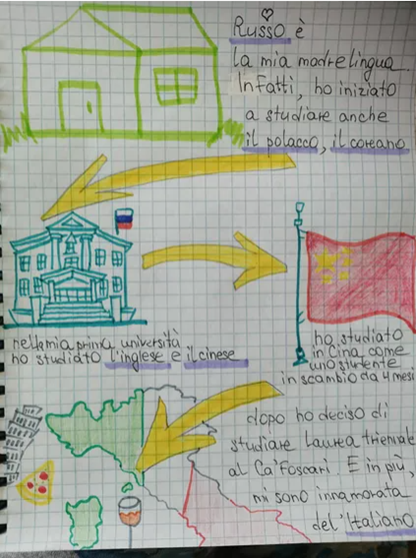

Figure 1. Visual language autobiography No. 2.

This student starts from the top drawing a house (languages: Russian to which they add Polish and Korean), then a school/university (languages: English and Chinese). There is a mention of a four month-study abroad program in the People’s Republic of China (language: Chinese) and finally the decision to study in Italy (language: Italian). From the bold yellow arrows the timeline seems very well defined. It can also be gathered that the student is curious about languages: school is not the only place where they are learnt (formal vs. formal and non-formal instruction). Two more aspects should be noted: firstly, the use of symbols, often used in chats communications as well, to convey meaning: a little heart above the mother tongue; a glass of red wine together with a slice of pizza and the leaning tower of Pisa to reinforce the image that Italy has around the world; secondly the use of flags or their colors to indicate a specific nation.

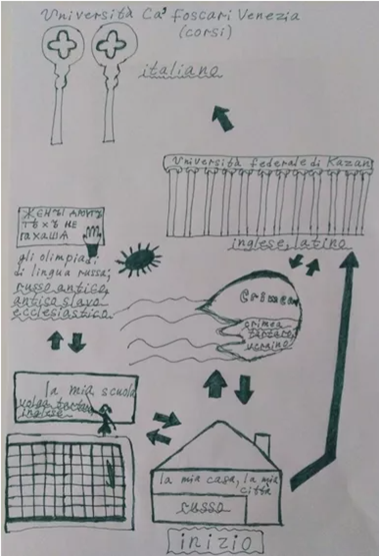

Figure 2. Visual language autobiography No. 3.

This student moves from bottom to top, starting from their house and family (language: Russian). Not far is the school where we can see a teacher next to the board (languages: Volga Tatar and English), then above on the left we see the Olympics for the Russian Language (languages: Old Russian, Ecclesiastical Old Slavic). After that, the image of the University (languages: English and Latin), then Venice, another university (language: Italian). Interesting are the arrows which link in both directions the places and the facts pictured. It is interesting to note how the school is portrayed in the form of a teacher pointing at the board. There is a substantial use of wording (in different alphabets) compared to the use of icons: it could show the importance of the written language in its acquisition and/or knowledge.

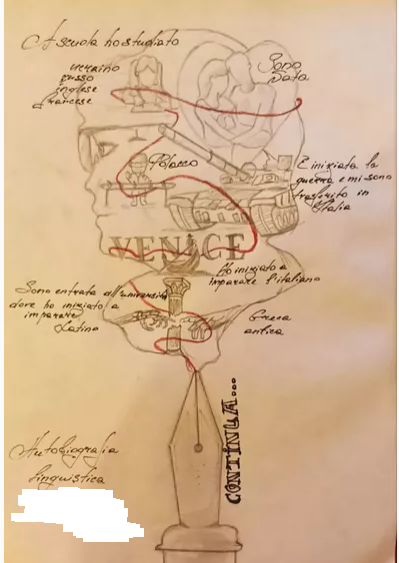

Figure 3. Visual language autobiography No. 5.

The timeline here is portrayed as a red thread: from birth, to school (languages: Ukrainian, Russian, English and French). Then the student mentions Polish, and subsequently the war that forces the person to flee to Italy where they enrol in University (languages: Italian, Latin, Old Greek). The red line ends into the fountain pen’s tip but on the side there is the writing “to be continued”. This is probably the more “artistic” biography collected in this study, where images have embedded multiple meanings and ways of reading it: the loving couple portraying the parents, the shape of the face on the side made by the ink, the revisited Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco, etc.

Through this type of task the learner has to contextualize their language learning experience in an intertwine of the micro and the macro level between complex systems: personal life and environment, schools, nations, and so on in a plurigraphic and plurisemiotic way.

Nonetheless when analysing these types of products, it should not be forgotten the distinction between an etic point of view (based on the researcher’s interpretations) and the emic one (based on the participants’ perspective), and therefore the potential divergence between the two (Melo-Pfeifer and Kalaja, 2019) that could lead to question the confidence of those interpretations. Moreover, visual language autobiography, due to the constraints of the piece of paper where they are drawn, can include less details compared to a narrative one and this also should be acknowledged by the SLA researcher.

4.2. Analysis of the composition on Italian language learning approach

Since the level of language competence was B1 of the CEFR, the second task proposed involved the reading of a text from a book in Italian where the writer, a non-native speaker, narrates her approach to the Italian language in a poetic way. This was used as a sort of prompt to make learners reflect on how they came close to the Italian language. Taking inspiration from the reading they were asked to write a text focussing on the same topic. Afterwards a qualitative thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) of the learners’ texts was done with the software MAXQDA. After the multiple cycle coding, the researcher found five (5) nodes (recurring topics).

4.2.1 Motivation

· “Volevo studiare in Italia” [“I wanted to study in Italy”]

· “Voglio tantissimo impararlo” [“I really want to learn it”]

· “Mi sono innamorata della lingua” [“I fell in love with the language”]

· “E anche è un’incredibile opportunità per me” [“It also is an incredible opportunity for me”]

4.2.2 First Contact

- Through family or beloved ones (3)

- Spontaneous (2)

4.2.3 Difficulties

- Comparing Italian with English at the beginning was manageable, but later it became a dilemma: “La mia esperienza nell’apprendimento della lingua Italiana è iniziato da comparazione tra l’italiano e l’inglese. Siccome ho pensato che se parli inglese tutte le due lingue si sembrano uguale e simile, non sarà troppo difficile apprendere l’altra. (...) Ma, sfortunamente, l’inglese è finito di essere il flagello della mia opportunità di studiare e immergermi nel’italiano autonomamente.” [“My experience in learning Italian started from the comparison between Italian and English. Since I thought that if you speak English and that both languages are equal and similar, it won’t be too hard to learn the other. (...) But, unfortunately, English became the plague of my opportunity to study and immerse autonomously in the Italian language.”]

- Difficulties in oral comprehension: “Nel primo tempo parlare ‘si’ o ‘no’ nel negozio era il problema grande per me.” [“At the beginning, saying ‘yes’ or ‘no’ in a shop was a big problem for me.”]

- War: “Nel febbraio di 2022 la guerra è iniziata. Era molto difficile emotivamente. C’erano tanti giorni quando leggevo le notizie e dopo non potevo fare niente tutto il giorno, qualche settimana non andavo all’università.” [“In February 2022, war started. It was very difficult emotionally. There were many days when I read the news and then couldn’t do anything for the whole day. For some weeks, I didn’t go to university.”]

- Moving to a new country with a different language: “Prima, avevo paura a trasportare la nostra famiglia lontana dai nonni a un posto dove parlavano un’altra lingua.” [“Before, I was scared of moving our family far from the grandparents to a place where they spoke another language.”]

- Personality: “Ma è difficile per me parlare. Io sono timida.” [“But it is difficult for me to speak. I’m shy.”]

4.2.4 Self-Effort

- “Autonomamente” [“Autonomously”]

- “Nella scuola media ha cominciato imparare italiano da un libro. Imparavo quando avevo il tempo libero e volevo (non sempre e non regolare).” [“In middle school, I started studying Italian by myself with a book. I studied when I had free time and wanted to (not always and not regularly).”]

- “Imparavo italiano con i tutori, iniziavo parlare con i lavoratori nei negozi e uffici pubblici in italiano.” [“I learned Italian with tutors. I started speaking with workers in shops and public offices in Italian.”]

- “Vai, M., vai! + emoticon of encouragement” [“Go, M., go!”]

4.2.5 Positive Results

- “Però, ho finalmente superato quella dilemma.” [“But, I finally overcame that dilemma.”]

- “E adesso, secondo me, ho migliorato mio italiano. Perché posso parlare, costruire le proposte, ascoltare e capire. Faccio gli errori, scrivo e leggo veramente male. Ma adesso sono migliore di me stesso 2 anni fa.” [“And now, in my opinion, I improved my Italian. Because I can speak, construct sentences, listen, and understand. I still make mistakes, I write and read really badly. But now I am better than I was 2 years ago.”]

- “Sono diventato felice.” [“I became happy.”]

- “Mi dà coraggio.” [“(It) gave me courage.”]

- “E oggi finalmente posso un po’ parlare.” [“And today, I can finally speak a little.”]

4.2.6. Emerging trends

What emerges is that there is a strong bond with emotions: desire, fear, love, courage, happiness. In Damasio’s (1994) words: “No cognitive achievement is free of emotions; the stronger the emotional involvement, the stronger are memories and knowledge”. In the texts, students show the power obtained by becoming competent in the language, in this case in Italian, as self-acknowledging and self-empowering as well: becoming proficient in a language allows one to accomplish different tasks that require language negotiation with others without relying on someone else, makes one independent, and, moreover, it can be considered a path to success in social relationships, academic studies and work. It also gives a key for the interpretation of the surrounding environment for those living in Italy.

4.3. Multilingual poetry

As the final task of this reflective plan, students who wanted could try their hands at composing a multilingual poem. The title proposed was: “I and my languages”. The aim of the activity was to recognize in their multilingualism a personal resource that can lead to use different languages to express the self. By way of example, follow three of the poems composed by the students:

4.3.1. Poem No. 1

Fa molto freddo, e le neve luccica sotto i piedi,

The morning and the night look just the same.

Вдали гудит электричка.

Sono sonno, e tutto intorno è come un sogno.

Ich muss gehen, aber es ist sehr schwierig:

Ведь дома тепло, и громко мурлычат коты.

Si sa di caffè e il cibo della mamma.

Non c’è posto migliore di casa.

Ich vermisse dich, mein Zuhause.

4.3.2. Poem No. 5

Cумне життя

Χωρίς οικογένεια και φίλους

and everything was left behind

как мимолетное виденье

cancella tutta la vecchia vita

Et ils disent la vérité quand les problèmes arrivent

puoi mettere tutta la tua vita in uno zaino

І завжди в такі моменти життя

Memento mori, sed vivere ne obliviscaris

As it can be seen both poems make use of various languages, creating artistically assonances and alliterations that break the limits of one specific language.

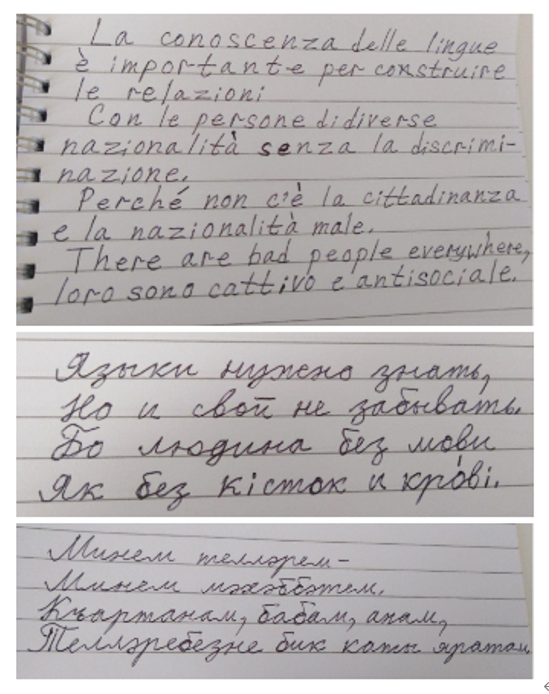

4.3.3. Poem No. 3

Figure 4. Poem No. 3.

But one student, after posting the picture of their poem (see Figure 4), adds a metacognitive explanation in Italian where they share their reflection on the work they have done:

“The first part is in Italian and English. The second part is in Russian and Ukrainian: it is necessary to know languages, but not forget (one’s own) mother tongue because a person without a language is like (a person) without bones and blood. The third part is in (Volga) Tatar and Crimean Tatar (my mother tongues): my languages are my love. My grandmother, my mother, my father, our languages I love a lot” (translated by the Author).

The last example is the clear realization of everything this work has been dealing with. At the end of the project this learner realizes how all the languages they know are part of them and how they are all important.

4.4. The final questionnaire

After the three tasks were completed, the instructor explained the choices made and the motivations that led to the planning of the activities the students had undergone. Students were asked to answer a quick questionnaire regarding their satisfaction. Table 1 displays the answer in the order they were received.

|

Italian |

English |

|

“È difficile perché è molto creativo, ma anche è molto interessante” |

“It is difficult, because it is very creative, but also very interesting” |

|

“Mi sono piaciuti tanto” |

“I really liked them” |

|

n/a |

“Thank you for this activities, I liked them so much, because I enjoy doing something creative and unusual. I lover creating self-biography (even if it doesn’t look good, because I am bad in drawing) and poem” |

|

“Secondo me questo buona idea, perché altri persone posso vedere quante lingue sanno” |

“I think this is a good idea, because other people can see how many languages they know” |

|

n/a |

“That it was interesting to do and to see how many languages there are in my life, because i was learning also French, German and Japanese but I know them on a very bad level” |

Table 1. Answers to the final question: “What is your opinion on the linguistic self-biography and the following activities proposed during the course?”

The words of the participants show that not only these multimodal and creative activities have been well received but also helped in raising consciousness about each individual linguistic repertoire and raised awareness of students’ multilingualism through the means of tasks where languages were used to narrate and express the self in a plurigraphic and plurisemiotic way. Art allows for decentering, multiperspectivism and uncovering layers of complexity (Gonçalves Matos & Melo-Pfeifer, 2020). A table follows, which summarizes the above content.

|

Task No. |

Tool |

Outcome feature(s) |

|

1 |

Visual linguistic autobiography |

(Self)-reflection on known languages: when, where and how they were learned |

|

2 |

Composition on Italian language learning approach |

Main topics: motivation, first contact, difficulties, self-effort, positive results. Strong link with emotions: desire, fear, love, courage, happiness |

|

3 |

Plurilingual poetry |

Free multilingual self-expression |

|

|

Final questionnaire |

Metacognitive reflection on the previous activities |

Table 2. Synopsis of the tools used and their outcome.

5. Conclusions

In this study we have seen the application of different activities during an Italian language online course of B1 level with international students. The limit of this study is the small number of participants and the fact that the introspective instruments used to collect data could be biased given that the authors decide what information to share and are further subject to the interpretation of the researchers. Moreover, data gathered by means of self-narrative can risk superficiality and lack depth, even if this study does not seem to be affected this way. As a matter of fact, it appears that the use of introspective tools and creative artistic tasks could foster language learning in the target language as well as raise identity awareness. Self-reflective practices also boost strategic and critical thinking applied to language learning.

Using Busch’s words:

“What interests us here is not so much the way linguistic skills are acquired and accumulated along the time axis; instead we wish to be able to trace how, by way of emotional and bodily experience, dramatic or recurring situations of interaction with others become part of the repertoire, in the form of explicit and implicit linguistic attitudes and habitualized patterns of language practices. It is only when we do not reduce language to its cognitive and instrumental dimension, but give due weight to its essentially intersubjective, social nature and its bodily and emotional dimension, that questions about personal attitudes toward language can be adequately framed” (Busch, 2015, p. 11).

Language learning is not merely a cognitive process, in fact positive experiences when learning languages bring deeper learning (Kramsch, 2009; Balboni, 2013).

There is a need to change perspective in the language classroom: specifically, what in the past was seen as “deficiency”, “lack of”, (negative) interference from the L1, should be used as a resource, as a trigger to promote language learning in the target language. Especially in a world that features increasing geographical and digital mobility Blommaert (2010, p. 5) proposes the shift from sociolinguistics of community to sociolinguistics of mobility: “a sociolinguistics of speech, of actual language resources deployed in real sociocultural, historical, and political contexts”.

Regardless of one’s linguistic background, pedagogies should prepare students for the new challenges of increased global mobility and contact zone interactions (Kimura & Canagarajah, 2017, p. 304).

“When we reflect upon an experience instead of just having it […] such reflection upon experience gives rise to a distinction of what we experience (the experienced) and the experiencing—the how” (John Dewey, 1916, p. 196).

References

Bagna, C., Machetti, S., & Barni, M. (2018). Language policies for migrants in Italy: Tension between democracy, decision-making and linguistic diversity. In M. Gazzola, T. Templin, & B.-A. Wickström (Eds.), Language Policy and Linguistic Justice: Economic, Philosophical and Sociolinguistic Approaches (pp. 477–498). Berlin: Springer.

Balboni, P. E. (2013). Il ruolo delle emozioni di studente e insegnante nel processo di apprendimento e insegnamento linguistico. EL.LE, 2(1), 7-30. https://doi.org/10.14277/2280-6792/1063

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. (2012). Arts based research. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230627

Beacco, J.-C., Byram, M., Cavalli, M., Coste, D., Cuenat, M. E., Goullier, F., & Panthier, J. (2016). Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe. Retrieved December 26, 2024, from https://rm.coe.int/16806ae621

Block, D. (2003). The social turn in second language acquisition. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Block, D. (2014). Moving beyond “lingualism”: Multilingual embodiment and multimodality in SLA. In S. May (Ed.), The Multilingual Turn (pp. 54–77). Oxon: Routledge.

Blommaert, J. (2008). Language, asylum, and the national order. Urban Language & Literacies, 50(4), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/600131

Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Busch, B. (2006). Language biographies: Approaches to multilingualism in education and linguistic research. In B. Busch, A. Jardine, & A. Tjoutuku (Eds.), Language Biographies for Multilingual Learning (pp. 5–18). Cape Town: PRAESA.

Busch, B. (2015). Expanding the notion of the linguistic repertoire: On the concept of Spracherleben - The lived experience of language. Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv030

Butler-Kisber, L. (2010). Qualitative inquiry. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526435408

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review, 2, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110239331.1

Candelier, M., & De Pietro, J.-F. (2012). FREPA: A framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and cultures: Competences and resources. Graz: European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML).

Candelier, M. (Ed.). (2003). L’éveil aux langues à l’école primaire. Evlang: Bilan d’une innovation européenne. Bruxelles: De Boeck-Duculot. https://doi.org/10.3917/dbu.cande.2003.01

Carbonara, V., & Scibetta, A. (2019). Oltre le parole: Translanguaging come strategia didattica e di mediazione nella classe plurilingue. In B. Aldinucci, V. Carbonara, G. Caruso, M. La Grassa, C. Nadal, E. Salvatore (Eds.), Parola: Una nozione unica per una ricerca multidisciplinare (pp. 491–509). Siena: Università per Stranieri di Siena. Retrieved December 26, 2024, from https://edizioni.unistrasi.it/public/articoli/660/files/44__carbonara_scibetta.pdf

Carbonara, V., & Scibetta, A. (2019). Translanguaging as a pedagogical resource in Italian primary schools: Making visible the ordinariness of multilingualism. In J. Won Lee & S. Dovchin (Eds.), The ordinariness of translinguistics (pp. 115–119). London: Routledge.

Carbonara, V., & Scibetta, A. (2018). Il translanguaging come strumento efficace per la gestione delle classi plurilingui: Il progetto ‘L’AltRoparlante’. Rassegna Italiana di Linguistica Applicata, 1, 65–82.

Cognigni, E. (2007). Vivere la migrazione tra e con le lingue: Funzioni del racconto e dell’analisi biografica nell’apprendimento dell’italiano come lingua seconda. Porto S. Elpidio: Wizarts.

Cognini, E. (2020). Le autobiografie linguistiche tra ricerca e formazione: Approcci e metodi di analisi. Italiano LinguaDue, 12(2), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.13130/2037-3597/15002

Cook, V. (1999). Going beyond the native speaker in language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 33(2), 185–209. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587717

Coppola, D., & Moretti, R. (2018). Valorizzare la diversità linguistica e culturale. Uno studio di caso. In C. M. Coonan, A. Bier, & E. Ballarin (Eds.), La didattica delle lingue nel nuovo millennio (pp. 397–412). Venezia: Ca’ Foscari. http://doi.org/10.30687/978-88-6969-227-7/024

Council of Europe. (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe Publishing. Retrieved December 26, 2024, from www.coe.int/lang-cefr

Council of Europe. (2010). A framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and cultures (CARAP/FREPA). Retrieved December 26, 2024, from www.ecml.at/CARAP-version3-FR-23062010

Council of Europe. (2018). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Companion volume with new descriptors. Retrieved December 26, 2024, from https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989

Cummins, J., & Early, M. (2011). Identity texts: The collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools. Stoke-on-Trent, UK: Trentham Books.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam’s Sons.

Della Putta, P., & Sordella, S. (2022). Insegnare l’italiano a studenti neo arrivati: Un modello laboratoriale. Pisa: ETS.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York: Macmillan.

Diadori, P., Palermo, M., & Troncarelli, D. (2009). Manuale di didattica dell’italiano L2. Perugia: Guerra Edizioni.

Dompmartin-Normand, C., & Thamin, N. (2018). Presentation. Lidil, 57, 4830. https://doi.org/10.4000/lidil.4830

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (Eds.). (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Harlow: Pearson.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2000). Task-based research and language pedagogy. Language Teaching Research, 4(3), 193–200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/136216880000400302

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based Language Learning and Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based language teaching: Sorting out the misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00231.x

Firpo, E., & Sanfelici, L. (2016). La visione eteroglossica del bilinguismo: Spagnolo lingua d’origine e Italstudio. Milano: Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto.

Franceschini, R. (2006). Unfocussed language acquisition? The presentation of linguistic situations in biographical narration. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, 31(3), 29–49.

Council of Europe. (2012). FREPA: A framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and cultures – Competences and resources. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe Publishing. Retrieved December 26, 2024, from https://www.ecml.at/Resources/ECMLresources/tabid/277/ID/20/language/en-GB/Default.aspx

García, O., & Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gonçalves Matos, A., & Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2020). Art matters in languages and intercultural citizenship education. Language and Intercultural Communication, 20(4), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1786917

Camilleri Grima, A, Candelier, M., Castellotti, V., de Pietro, J-F., Lörincz, I., Meissner, F-J., Molinié, M., Noguerol, A., & Schröder-Sura, A. (2012). A framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and culture (FREPA). Graz, Austria: European Center for Modern Languages / Council of Europe Publishing.

Holmes, P., Fay, R., Andrews, J., & Attia, M. (2016). How to research multilingually: Possibilities and complexities. In Research Methods in Intercultural Communication: A Practical Guide (pp. 88–102). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Jaspers, J., & Madsen, L. (2016). Sociolinguistics in a languagised world: Introduction. Applied Linguistics Review, 7(3), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2016-0010

Jaspers, J., & Malai Madsen, L. (Eds.). (2018). Critical Perspectives on Linguistic Fixity and Fluidity: Languagised Lives (1st ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429469312

Jewitt, B. (Ed.). (2009). Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. London: Routledge.

Kalaja, P., & Melo-Pfeifer, S. (Eds.). (2019). Visualising Multilingual Lives: More Than Words. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Kalaja, P., & Pitkänen-Huhta, A. (2020). Raising awareness of multilingualism as lived – In the context of teaching English as a foreign language. Language and Intercultural Communication, 20(4), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1786918

Kalaja, P., Alanen, R., & Dufva, H. (2008). Self-portraits of EFL learners: Finnish students draw and tell. In P. Kalaja, V. Menezes, & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Narratives of Learning and Teaching EFL (pp. 186–198). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kalaja, P., Alanen, R., & Dufva, H. (2011). Teacher trainees’ beliefs about EFL learning in the light of narratives. In S. Breidbach, D. Elsner, & A. Young (Eds.), Language Awareness in Teacher Education: Cultural-Political and Social-Educational Perspectives (pp. 63–78). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Kimura, D., & Canagarajah, S. (2017). Translingual practice and ELF. In J. Jenkins, W. Baker, & M. Dewey (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of English as a Lingua Franca (pp. 291–304). London: Routledge. https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315717173.ch24

Kramsch, C. (2009). The Multilingual Subject. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kress, G. (2009). Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

Kubokawa, J. M. (2023). The multilingual poetry task: Innovating L2 writing pedagogy in the secondary classroom. Journal of Second Language Writing, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2023.101039

Long, M. (1985). A role for instruction in second language acquisition: Task-based language teaching. In K. Hyltenstam & M. Pienemann (Eds.), Modelling and Assessing Second Language Acquisition (pp. 77–79). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Long, M. (2015). Second Language Acquisition and Task-Based Language Teaching. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2016). Second Language Research: Methodology and Design. London: Routledge.

Maher, J. C. (2017). Multilingualism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mandrona, A. (2010). Children’s poetic voice. LEARNing Landscapes, 4(1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v4i1.368

Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2021). Exploiting foreign language student teachers’ visual language biographies to challenge the monolingual mind-set in foreign language education. International Journal of Multilingualism, 18(4), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1945067

Menegale, M. (2022). Il concetto di benessere nell’insegnamento delle lingue: nuove linee di ricerca. Studi di glottodidattica, 8, 132–143. https://doi.org/10.15162/1970-1861/1537

Menezes, V. (2008). Multimedia language learning histories. In P. Kalaja, V. Menezes, & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Narratives of Learning and Teaching EFL (pp. 199–213). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mercer, S. (2011). The self as a complex dynamic system. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 57–82. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2011.1.1.4

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ministero dell’Istruzione e del Merito. (2020). Gli alunni con cittadinanza non italiana: A.S. 2018/2019. Gestione Patrimonio Informativo e Statistica. Retrieved December 26, 2024, from https://www.mim.gov.it/documents/20182/0/Rapporto+-+Gli+alunni+con+cittadinanza+non+italiana_as_2018-2019.pdf/f1af9f21-cceb-434e-315e-5b5a7c55c5db?t=1616517692793

Molinié, M. (2015). Recherche biographique en contexte plurilingue: Cartographie d’un parcours de didacticienne. Actes académiques, Série Langues et perspectives didactiques. Paris: Riveneuve.

Moore, D., Oyama, M., Roy Pearce, D., & Kitano, Y. (2022). When awakening to languages meets plurilingual poetry: Aesthetic explorations in an elementary school in Japan. Leseforum, 1, 1–17. Retrieved December 26, 2024, from https://www.leseforum.ch/sysModules/obxLeseforum/Artikel/756/2022_1_fr_moore_et_al.pdf

Morin, E. (2017). La sfida della complessità. Le Lettere.

Muller, S. (2022). Visual silence in the language portrait: Analysing young people’s representations of their linguistic repertoires. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(10), 3644–3658. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2022.2072170

Nikula, T., & Pitkänen-Huhta, A. (2008). Using photographs to access stories of learning English (pp. 171–185). In P. Kalaja, V. Menezes, & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Narratives of learning and teaching EFL. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Norris, S. (2004). Analysing multimodal interaction: A methodological framework. London: Routledge.

Nuzzo, E., & Santoro, E. (2017). Pragmatica dell’italiano come lingua seconda/straniera. E-JournALL, 4(1), 1–145. http://dx.doi.org/10.21283/2376905X.7.116

Nuzzo, E., & Vedder, I. (2019). Lingua in contesto: La prospettiva pragmatica. AITLA. Retrieved December 26, 2024, from http://www.aitla.it/images/pdf/eBook-AItLA-9.pdf

Ortega, L. (2014). Ways forward in a bilingual turn in SLA (pp. 32–53). In S. May (Ed.), The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education. Routledge.

Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm008

Pennycook, A., & Otsuji, E. (2014). Metrolingual multitasking and spatial repertoires: ‘Pizza mo two minutes coming’. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 18(2), 161–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12079

Prasad, G. (2018). Making adolescents’ diverse communicative repertoires visible: A creative inquiry-based approach to preparing teachers to work with (im)migrant youth. Lidil, 57, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4000/lidil.4867

Prendergast, M. (2009). “Poem is What?” Poetic Inquiry. International Review of Qualitative Research, 1(4), 541–568. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2009.1.4.541

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Skehan, P. (1998). Task-based instruction. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 18, 268–286. https://doi.org/0.1017/S0267190500003585

Sordella, S., & Andorno, C. M. (2017). Esplorare le lingue in classe: Strumenti e risorse per un laboratorio di éveil aux langues nella scuola primaria. Italiano LinguaDue, 2, 162–228.

Vallejo, C., & Dooly, M. (2019). Plurilingualism and translanguaging: Emergent approaches and shared concerns. Introduction to the special issue. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1600469

Williams, C. (1996). Secondary education: Teaching in the bilingual situation (pp. 39–78). In C. Williams, G. Lewis, & C. Baker (Eds.), The language policy: Taking stock. UK: CAI Language Studies Centre.

Willis, J., & Willis, D. (Eds.). (1996). Challenge and change in language teaching. Oxford: Heinemann.